How my journey to Sogut began

My journey to Sogut began in lockdown 2021. Gathered together in front of the TV I somewhat reluctantly set out for the first time to explore with the family our first ever Muslim drama series – Kurulus Ertugrul. As part of my lifelong interest in the interactions of civilisation I was always fascinated by the Ottoman Empire, and in particular their approach to the birth of modernity. I was also interested in institutions founded in earlier Muslim civilisations. In the Ottomans, these two interests came together. At first, I was simply curious about why this series was so highly praised by so many, Muslim history enthusiasts, Islamic scholars, and others alike.

I wasn’t really into Netflix back then, but during the quiet of lockdown, watching Ertugrul Gazi (d. 1280/82) in action became a daily routine – some 500 episodes to watch. Since then, my eldest has gone on to watch the entire Kurulus: Osman series (or “Osman” for short), which is the sequel to Kurulus Ertugrul, while the rest of the family hasn’t shown much interest, aside from the occasional questions like, “Has Ertugrul died?” or “What happened to Bamsi and Turgut?” Kurulus Osman charts the life of Osman Gazi (d. 1324), Ertugrul’s youngest son, who is the official founder of the Ottoman Empire, which is named after him.

I last visited Turkiye with my wife some 16 years ago, in 2009. We stayed in Istanbul’s old quarter, the Sultanahmet area, and headed out for trips to places like Edirne, on the border with Greece and Bulgaria, about 143 miles north west of Istanbul. The reason for visiting Edirne was to see the biggest mosque dome in Turkiye at the time, the great Selimiye Camii (mosque), completed in 1575, under one the greatest architects of all time, Mimar Sinan. Edirne was for a century the capital of the Ottoman Empire, after Bursa and before Istanbul.

Fast forward to August 2025, and we decided to visit Turkiye, for a 12 day stay in Istanbul, Bursa and Sogut.

Having visited Istanbul before, I didn’t feel the urge to see “everything” this time. On our previous trip, we must have visited more than 50 mosques, so that particular obsession had long since run its course. This time, however, a new obsession had taken hold, though not mine, but the children’s: swimming. Every day we went for a swim, and we chose hotels that offered at least an indoor pool.

We also swam in the Black Sea on a day trip to the north coast outside Istanbul. Still, for the children, it was important to balance fun with cultural experiences. Between their usual obsession over Clash Royale and talk of “Evil Valkyrie” and “Mini Pekka,” we tried to make sure, by God’s grace, they also had the chance to appreciate the beauty of the city’s great mosques, wander through its lively bazaars, and enjoy its stunning scenery.

The capitals of the Ottoman Empire

Whilst Istanbul, or Constantinople as it was named then, became the capital of the Ottoman Empire after it was conquered under Sultan Mehmed II (known as “Mehmed the Conqueror” or “Fatih Sultan Mehmed”) on 29 May 1453, Bursa was the first capital of the Ottoman Empire, and where some of the earliest Ottoman sultans, including Osman, are buried. Sogut, a small, somewhat sleepy town today, was where Ertugrul is buried and was the precursor to Bursa. It was in Sogut that Ertugrul, and Osman to an extent, laid down roots, establishing the frontier settlement that later blossomed into one the biggest and most successful empires in history. Ertugrul’s tomb remains the main focal point of Sogut.

For centuries after the 1453 conquest, the Ottomans commonly called Istanbul “Konstantiniyye” (“from Constantinople”) in official documents, though people also used other names informally, such as “Istanbul” (derived from the Greek phrase “eis tin polin” – “to the city”).

In everyday speech, “Istanbul” had already been widely used long before the 20th century. After the Turkish Republic was founded in 1923, reforms pushed for standardisation. In 1930, the Turkish government officially adopted “Istanbul” as the city’s name, and international postal services were instructed to stop using “Constantinople.”

The name “Constantinople” comes from the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, who re-founded the city Byzantium as his new capital in 330 AD. The name is derived from the Greek “Konstantinoupolis”, which means “City of Constantine.” Before this, the city was known as “Byzantium,” named after its legendary founder Byzas. Byzas is traditionally said to have founded Byzantium in 667 BC. According to legend and ancient sources (such as coins and archaeological evidence), Byzas was a Greek leader from Megara who settled the city on the European shore of the Bosporus after consulting the oracle at Delphi.

Istanbul holds an endearing place for Muslims. The Prophet is reported to have said, “Verily, Constantinople will be conquered. What a wonderful leader will its leader be, and what a wonderful army will that army be!” (reported by Imam Muslim). This prophecy has given the city a special historical and spiritual significance, long before it became the Ottoman capital. The city is also indirectly mentioned in the Qur’an in Surah “The Romans” (30:2-4), which refers to the Romans (Byzantines): “The Romans have been defeated, in a nearby land. But they, after their defeat, will overcome, within a few years. Allah’s is the command, before and after; and on that day the believers will rejoice.” At the time, the Byzantines had suffered defeat by the Persians, but divine promise foretold their eventual victory, showing God’s control over the course of history. Together, these references underscore Istanbul’s spiritual and historical importance to Muslims, making it more than just a city of grand architecture and bustling streets; it is a symbol of prophecy, perseverance, and divine promise.

By the time Istanbul was conquered in 1453, much of the surrounding region had already come under Muslim rule, creating a strong strategic and cultural foothold for the Ottomans. The city’s capture was not an isolated event but the culmination of decades of expansion, linking the Ottoman heartlands in Anatolia and the Balkans with this historic crossroads between Europe and Asia. This journey began even in the days of the Prophet. The Companion Ayyub al-Ansari, the flag bearer of the Prophet, who died during the first Muslim siege of the city in the 670s, is buried just 4 miles north of the Hagia Sofia in today’s Istanbul. The area is now named after him: Eyup Sultan district. It is a reminder of the deep historical and religious connections that predate the Ottoman conquest.

In fact, Islam was already present in most regions of Turkiye and unified under Seljuk rule (known as the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum) well before the Ottomans came to power. By the 13th century the Seljuk Sultanate began to weaken due to internal conflicts, fragmentation, and external pressures. The Mongol invasions forced the Seljuk Empire to become a vassal state under the Mongols. The Mongols who invaded the Seljuk Empire were not Muslims at the time of their invasion, though several decades later some Mongol rulers converted to Islam such as Berke Khan (a grandson of Genghis Khan). Over time, the Seljuk central authority weakened and eventually fragmented into numerous smaller principalities known as “beyliks.” Among these were the Ottomans (from Ertugrul and Osman), who gradually rose in power. They first replaced the Mongols as the dominant force in Anatolia, then reunified much of the former Seljuk lands, though some independent beyliks remained for quite some time until the rule of Mehmed II (d.1481) around the mid-15th century. From there, the Ottomans expanded into the rest of Anatolia (e.g. Constantinople) and the Balkans, a region then divided among various powers, including the Byzantine Empire, the Bulgarian Empire, and the Serbian Empire. It was only under Ottoman rule that Islam spread into the Balkans, reaching places such as Bosnia, Kosovo, Bulgaria, and Cyprus. To this day about 11% of Bulgaria is Muslim, 51% of Bosnia is Muslim and 93% of Kosovo’s population is Muslim. Northern Cyprus, which is controlled by Turkiye, is 97% Muslim.

Climate

The temperature during our stay was warm, consistently staying around 29-31°C during the day and dropping to about 24°C at night. Istanbul generally doesn’t get as hot as the southern beach resort regions of Turkiye. It rained lightly on a couple of days, but only for short periods. On our previous trip we saw flash flooding near the Museum of the History of Science and Technology in Islam, and narrowly escaped being swept away by gushing flood water on a steeply sloped road. Memories of the experience came back as we walked past the area which is below the Topkapi Palace and beside the Gulhane Park (equivalent to London’s Hyde Park in that it provides a “green lung” to the city, but is much smaller, only about 10% the size of Hyde Park). Thankfully no flash flooding this time. On most days there was a refreshing breeze, which helped take the edge off the heat.

Having visited Istanbul before, we couldn’t help but make comparisons with our previous experience. Overall, the city felt cleaner and there seemed to be less of the pushy or guilt-driven sales tactics we experienced before. That said, we did notice some pockets of homelessness, though begging was rare. The conditions of roads were very good. I saw hardly any potholes on any major road, though the roads and pedestrian walking paths in Sultanahmet could be improved. The road traffic in some parts of Istanbul was horrendous at times, but somehow the hoards of taxi drivers seem to find their way through. The honking is much less than in other countries, and driving rules are quiet strictly adhered to.

Getting around

For ease of travel, we relied primarily on taxis, always checking that the meter was running. Currently, the rate stands at around 40 TRL per kilometre (roughly 75p). Drivers varied in professionalism, though a common habit we noticed was steering and changing gears with one hand while holding a mobile phone with the other. The “Bitaksi” app proved excellent – you have the option of paying by cash, the taxis arrived quickly, and it offered a helpful fare estimate, which was especially useful when we hailed a cab directly from the roadside, often the most convenient option.

Public transport, however, remains underdeveloped and not particularly convenient. Underground stations and trams are not well marked and not always in the right places. The hilly terrain and cramped conditions don’t necessary help with public transport in areas such as Sultanahmet, Beyoglu, Taksim and others. Bursa was similar. The bus from Mudanya didn’t get us into the Bursa city centre, so we had to take a local taxi from the bus depot some 2-3 kilometres away.

Food

The variety of food was somewhat limited, which was surprising for a city like Istanbul, given its cosmopolitan character and rich history. Turkish cuisine, much of which is already widely available in the UK, dominated, often served in a fast-food style. Other international options do exist, but they seemed to take some effort to find and are far less accessible. Alongside Turkish food, we ate Bangladeshi and Pakistani cuisine, as well as the usual Burger King and McDonalds. The good news is that finding halal food isn’t an issue. In the modern shopping malls there was much more variety. Burger King and McDonalds were being boycotted by some in solidarity with the people of Gaza as we learnt from speaking to locals, but there were, still, plenty of people eating there too.

In tourist areas and supermarkets alcohol is readily available, but in many local neighbourhoods and family-run restaurants it was notably absent, reflecting the city’s diverse but often conservative social fabric. This contrast between cosmopolitan openness and traditional restraint seemed to capture something essential about Istanbul itself – a place where modernity and faith, globalisation and local identity, constantly coexist and negotiate space.

Hospitality of the Turkish people

We generally found Turkish people to be warm and hospitable. In Istanbul, however, where locals are so accustomed to tourists, the warmth often felt more professional than personal, more like a polished, corporate friendliness than genuine affection. This is to be expected. Compared to our previous visit, English proficiency was noticeably higher, with hotel staff and many taxi drivers able to converse comfortably. One striking difference from the UK was the prevalence of cigarette smoking by both men and women, which remains far more common in Istanbul.

Turkish culture and religion

I’ve always found Turkiye’s culture and history very interesting. It has so many sustained influences from all directions: Arab, Balkan, Greek, Russian (Caucus region) and wider Mediterranean. Many words spoken in Turkiye have spread across the world. On our visit to the Topkapi Palace I was pleasantly surprised to learn that the word “Toki” is the same word used in Bengali for head hat. “Sepahi” in Turkish for cavalry/army is the same in Bengali. Interestingly, many commonly used words in the English language like “yogurt,” “kebab,” “caviar,” “pastrami,” “kiosk,” “sofa,” “caravan,” “tambourine” etc. are Turkish words in origin. In the book, Ottoman Studies by Ilber Ortayli, which I bought from a bookshop in Istanbul, you can truly get a sense of the colossal impact in both directions of countries like Bulgaria, which is deep and complex, spanning for centuries.

The Turkish language has been around for over 1200 years. It had major influences from Arabic and Persian during the Seljuk and then Ottoman periods. During the Ottoman periods, Turkish was written in a version of the Arabic script and heavily infused with Persian and Arabic vocabulary. However, after the founding of the Republic of Turkiye in 1923, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk led a major language reform, which, in 1928, introduced the Latin alphabet replacing the Arabic script, which remains to this day. Turkish belongs to the Turkic language family, which includes languages spoken across Central Asia, such as Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan.

Turkish religious culture is a blend of deep historical roots, modern secularism, and regional diversity, making it both rich and complex. Ramadan is widely observed. Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, which they call “Bayram” derived from Old Turkic for “joyous day” predating Islam (a term that astonished me when I first heard of it in my early 20s), are major celebrations involving family gatherings, charity, and feasting – just like anywhere else. The azan (call to prayer) can be heard five times a day without any trouble, in every town, city and locality we visited. Religious attire like headscarves is common though attitudes toward it vary. Respect for elders, hospitality, and modesty which are rooted in Islamic teachings are widely observed in Turkish society. Halal food practices are also common, even among the seemingly less religious families, influencing cuisine and food preparation.

Sunni Islam is the dominant tradition, comprising over 90% of the population, with most adherents following the Hanafi school of Islamic law. I believe that the “cosmopolitan” and historically rich Hanafi fiqh, as practiced in Turkiye, offers in my view a more relevant and productive framework for Muslims in the UK than the more “regionally focused” or “sectarian” Barelvi, Deobandi or Ahle Hadith traditions prevalent in South Asia. Another important reason is what I suspect is a stronger influence of Maturidi theology in Turkiye, which offers a living and adaptable framework for modern Islamic thought. Whilst I don’t have empirical evidence for this, the growing body of Maturidi scholarship in Turkiye suggests a theological environment conducive to balanced and intellectually rigorous Islamic thought. This kind of balanced theological reasoning is largely absent in South Asian contexts, including in the UK, where religious thought tends to lean either towards hadith literalism or a sectarian form of Ash’arism. Moreover, Turkiye’s European social and cultural milieu aligns more closely with the UK’s socio-cultural context than South Asia’s. The remaining 10% of Muslims are Shia, Alevi, Jafari and Alawite.

Even though Turkiye is officially secular, religion still plays a big role in everyday life for many people. In cities like Istanbul, we found a more modern and secular vibe, while rural and conservative areas such as Sogut, we found tended to hold more on to tradition. This mix creates a really interesting cultural landscape, where modern ideas and deep-rooted religious and national heritage often overlap and sometimes clash. Turkiye is kind of like a crossroads where politics, religion, and generational shifts all meet, and the country is constantly figuring out how to balance its Islamic past with its secular present.

Turkish history has also had significant cultural impact on the West. We all know Dracula, a fictional horror character in Western genre. What we probably don’t know, and I only learnt about it from a 2020 Netflix docudrama “Rise of Empires: Ottoman – Mehmed vs Vlad,” is that the story of Dracula was inspired by a real historical figure: Vlad III, also known as Vlad the Impaler or Vlad Dracula, and his brutal resistance against the Ottoman Empire’s expansion into Eastern Europe. His enemy was no less than the great Fatih Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror.

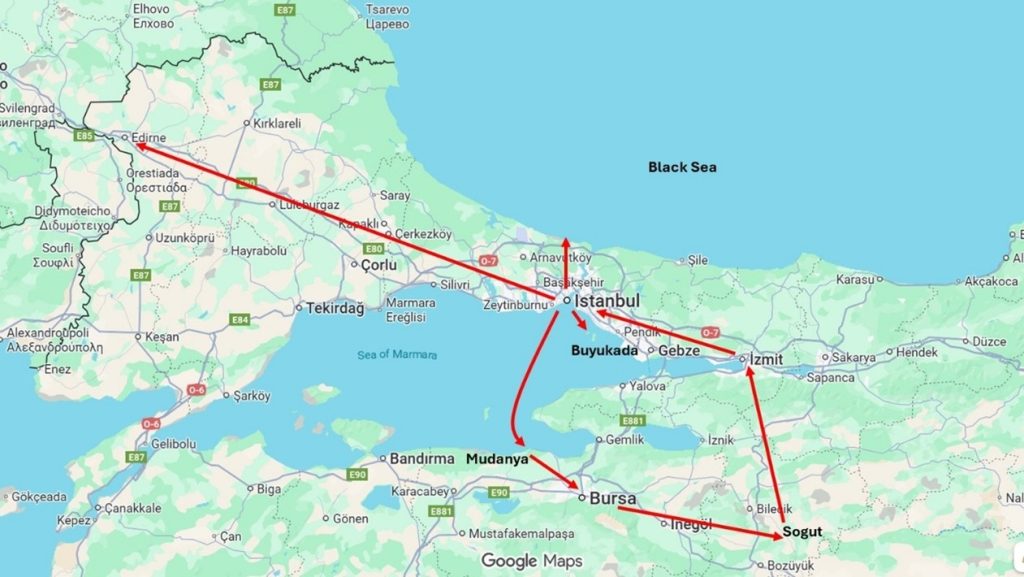

Map of places outside of Istanbul we visited (including visit to Edirne in 2009).

A birds eye view of the old city walls of Istanbul, taken from a poster at Istanbul International (IST) airport.

Prominent places and landmarks we visited

Topkapi Palace

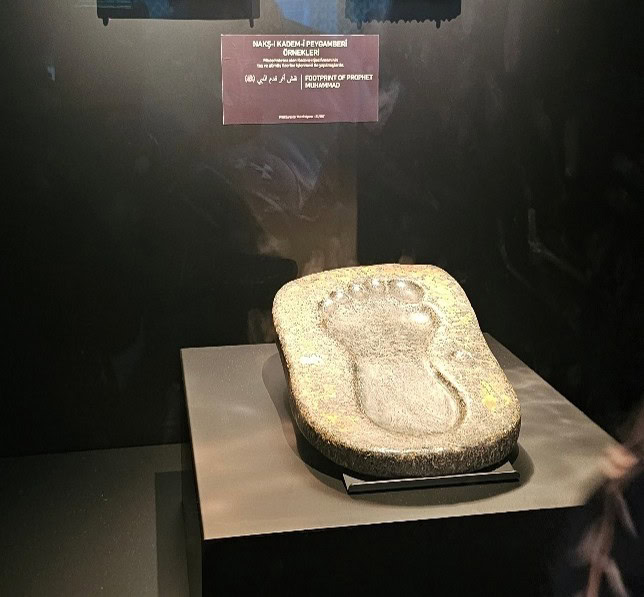

Topkapi Palace, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is a grand Ottoman imperial complex built starting in 1459 under Sultan Mehmed II, shortly after the conquest of Constantinople. It served as the primary residence and administrative centre of Ottoman sultans for nearly four centuries. The palace has many interconnected courtyards, pavilions, gardens, and service buildings arranged in a hierarchical layout. The palace also now houses religious relics, such as the reported foot imprint and hair of the Prophet. Its many buildings integrates Islamic, Byzantine, and European influences, with extensive use of Iznik tilework, carved marble, and intricate wood and stone decoration. It also includes private residential areas such as the Harem, along with ceremonial and administrative spaces. From the back of the Topkapi Palace you can see stunning views of the Bosphorus, the Asia side of Istanbul as well as views of the old city wall of Constantinople (pictured below). We also marvelled looking at the centuries-old (possibly 500-600 years old), hollowed tree (pictured below) in one of the courtyards, which I distinctly remember seeing the last time I visited. The tree is still in good health.

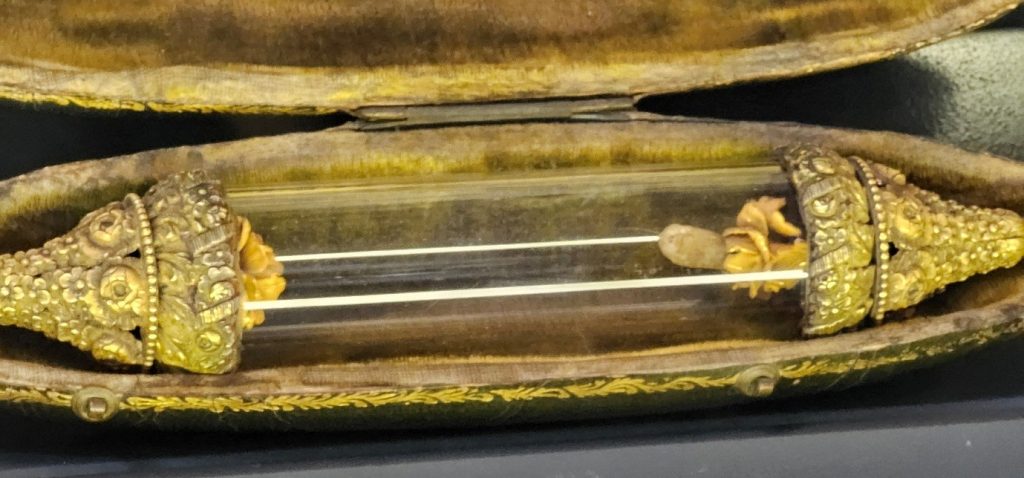

Among one of the most remarkable exhibits at the Topkapi Palace is the collection of sacred relics, which includes what is believed to be an imprint of the Prophet’s blessed foot – similar to the one in the Eyup Sultan Mosque. Putting aside questions of authenticity, standing before it is a profoundly humbling experience. The preservation of such relics within the heart of the Ottoman imperial complex also underscores how central love for the Prophet was to the Empire’s spiritual and cultural identity.

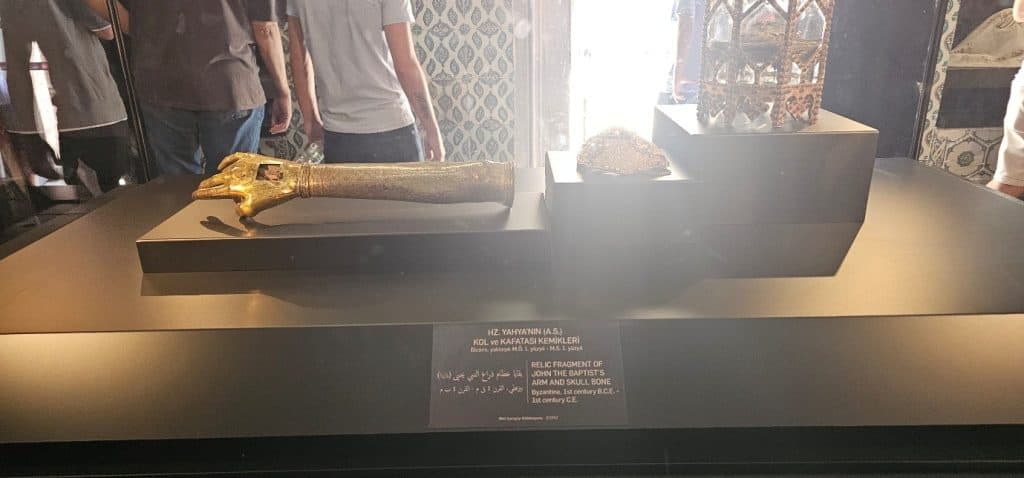

Reportedly a relic of the Prophet Yahya’s (John the Baptist) arm and bone.

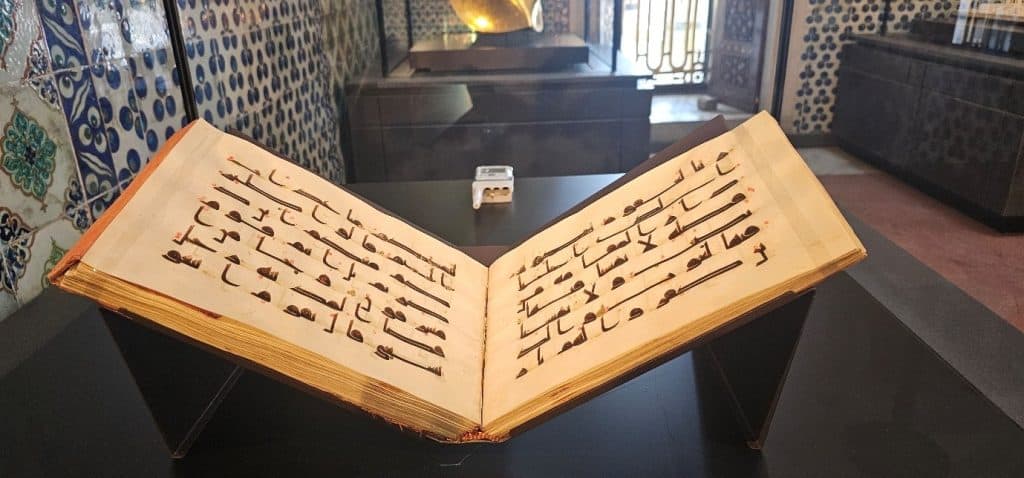

An early Qur’an in Kufic script. Kufic is the earliest form of Arabic calligraphy, originating from the city of Kufa in southern Iraq. It is characterised by its highly angular, geometric, and rectilinear letterforms, focusing on horizontal and vertical lines with a distinct lack of curves. Kufic was widely used from the 7th to 11th centuries and was the preferred script for writing early copies of the Qur’an and for architectural decorations.

The Topkapi Palace Museum houses an extraordinary collection of historical artefacts, including garments worn by high-ranking officials of the Ottoman Empire. Interestingly, the richly embroidered fabrics and ornate designs of Ottoman attire could easily be mistaken today for the kind of elaborate outfits worn at South Asian weddings.

Blue Mosque (Sultanahmet Camii)

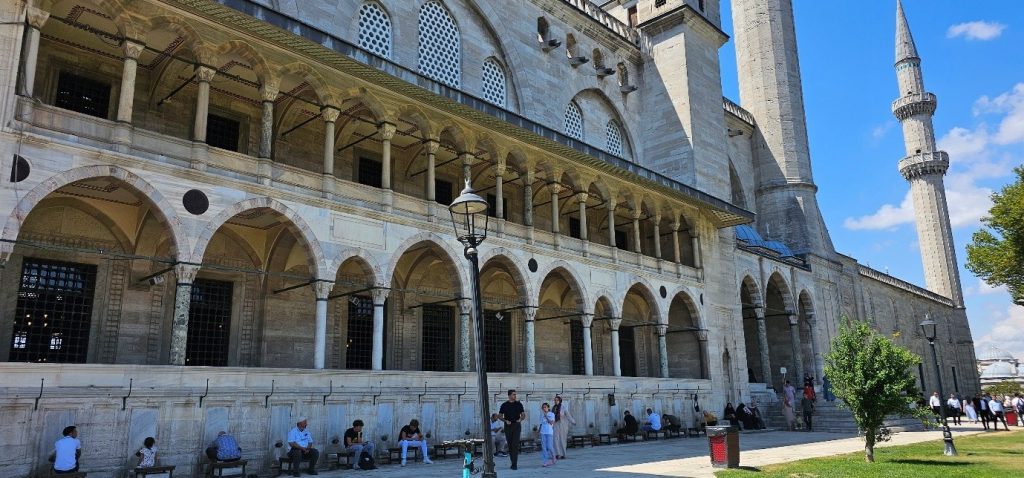

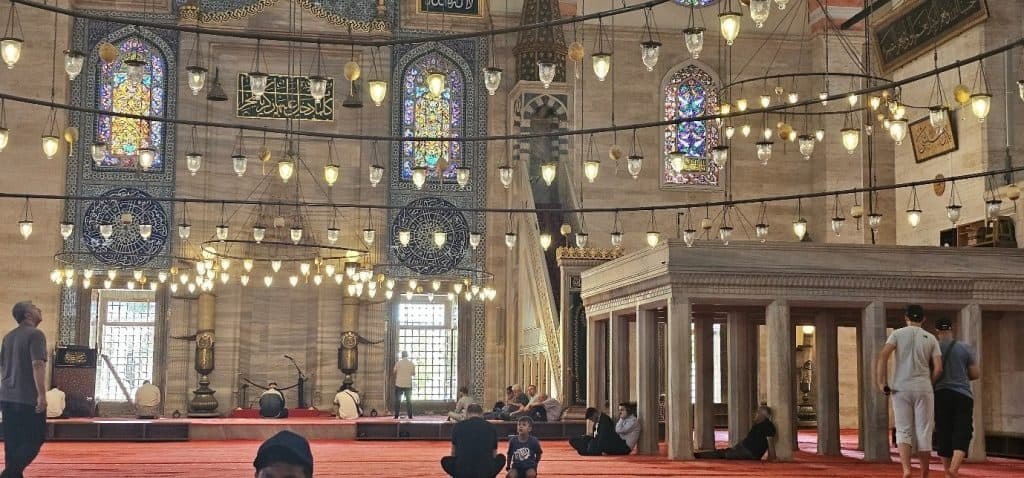

The Blue Mosque, also known as the Sultan Ahmed Mosque or Sultanahmet Camii, was built between 1609 and 1616 in Istanbul under Sultan Ahmed I. It can accommodate about 10,000 worshippers for salah. Built primarily to serve as a grand place of worship and also to rival the nearby Hagia Sophia, symbolising the power and glory of the Ottoman Empire. It is famous for its stunning interior adorned with over 20,000 handmade blue Iznik tiles, giving it its iconic name. Architecturally, it features one large central dome, six slender minarets, which is a rare number that initially caused controversy, and multiple smaller domes, blending Islamic and Byzantine styles inspired partly by the nearby Hagia Sophia. The controversy arose because at the time, the only mosque with six minarets was the Masjid al-Haram in Makkah. The Blue Mosque having six minarets was seen as controversial or even presumptuous since it matched the number of minarets of the sacred mosque in Makkah.

According to legend, this happened due to a misunderstanding: Sultan Ahmed I supposedly wanted “altin minaret” (gold minarets), but the architect heard “alti minaret” (six minarets). To resolve the controversy and maintain the perception of sanctity, a seventh minaret was added to the Masjid al-Haram. This made the Blue Mosque unique in having six minarets, which is a rare feature for an Ottoman mosque

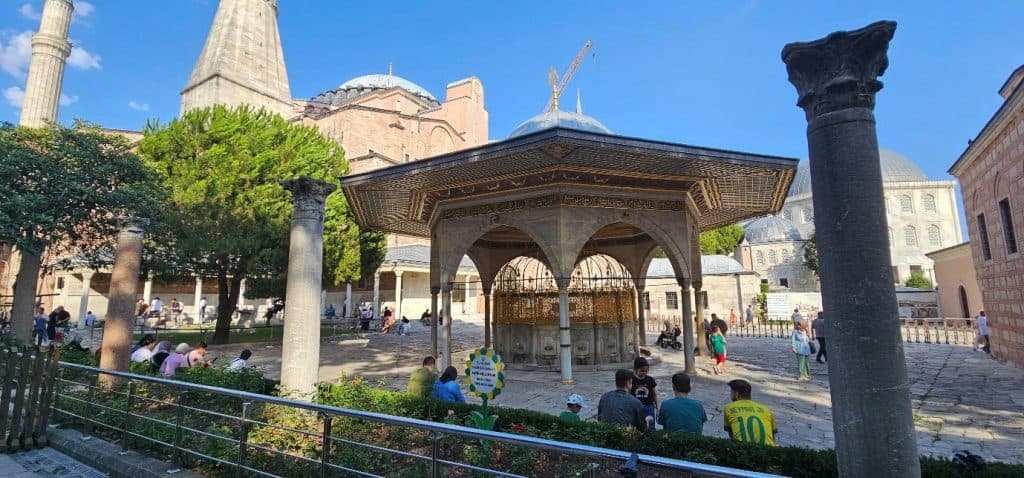

Beautiful courtyard of the Blue Mosque, with spectacular views, angles and open space for children (and adults) to roam about.

Incredibly high ceilings and beautiful domes and arches with Quranic script.

Back of the Blue Mosque lit up in blue in what looks like white light but the blue tiles on the mosque make it look bluer than it is in the daytime.

Hagia/Aya Sophia

The Hagia Sophia in Istanbul is a world renowned, monumental architectural masterpiece originally built as a Byzantine cathedral in 537 AD under Emperor Justinian I. It is renowned for its massive central dome, innovative use of pendentives allowing a circular dome over a square base, and luxurious marble interiors. After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, it was converted into a mosque, with Islamic features like minarets, a mihrab, and minbar added while preserving much of its Byzantine character. In 1935, it became a museum, and in 2020 it was again designated as a mosque. We prayed ‘Asr there and after the prayer, the imam prayed for Gaza and the people of Palestine.

Sultanahmet Square and Hippodrome

The Hippodrome area has been vastly improved since our last visit. The paving is beautiful and the whole area has a very friendly atmosphere. The Sultanahmet Square contains many relics. In the photo you can see the Egyptian Obelisk, which was originally erected by Pharaoh Thutmose III around 1500 BC in Egypt, it was brought to Constantinople by Emperor Theodosius in the 4th century AD. It is made of pink granite and mounted on a marble pedestal decorated with relief sculpture. Though it broke during transport, the upper part remains standing in the Hippodrome. The Serpent Column is a bronze column originally created to celebrate the Greek victory over the Persians in the 5th century BC. It was brought from Delphi to Constantinople by Constantine the Great. Much of its serpent head decoration was destroyed in the 1700s, but the column base remains.

The Sultan Ahmed Mausoleum, located near the Blue Mosque, contains the tombs of around 36 people, including several Ottoman sultans (Sultan Ahmed I, his sons Osman II, Ahmed I and Murad IV), other princes (“sehzades”) and royal children.

Kuyuk Aya Sofia

Also known as the Little Hagia Sophia, Kuyuk Aya Sofia is a historic mosque which was originally built as the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus during the Byzantine era. Constructed in the early 6th century under Emperor Justinian I, it predates the famous Hagia Sophia and is considered its architectural precursor. It is a UNESCO world heritage site.

The building features a compact, octagonal design with a central dome, embodying early Byzantine architectural styles. After the Ottoman conquest in 1453, the church was converted into a mosque, which it remains today, retaining many of its Byzantine architectural elements alongside Islamic features. However, I did not see the mosque as approaching anywhere near the splendour or grandeur of the Hagia Sofia. The mosque has a very old (and no longer used) wudu area with an old water pump within the mosque.

Grand Bazaar

The Grand Bazaar (“Kapalicarsi”) in Istanbul is one of the largest and oldest covered markets in the world, covering over 30,700 square meters with 61 covered streets and more than 4,000 shops. It attracts between 250,000 and 400,000 visitors daily, making it a major commercial and tourist hub. It is absolutely extraordinary. We visited the bazaar a few times, both on the outskirts as well as travelling through it. Luckily, while this is a place renowned for getting scammed very easily, we managed to haggle well and bought a few gifts at reasonable prices.

The core of the Grand Bazaar was constructed starting around 1461, shortly after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, under Sultan Mehmed II (“Fatih Sultan” or “Mehmed the Conqueror”). It was originally built to generate revenue for the upkeep of the Hagia Sophia Mosque. The bazaar began as a complex of two main buildings called “bedestens,” which were domed, fireproof structures where valuable goods like textiles, silk, jewels, and precious metals were stored and traded. Surrounding the bedestens, a maze of vaulted streets and alleys developed over centuries, creating a sprawling covered marketplace.

The shops in the Grand Bazaar are still traditionally divided by the type of goods, such as jewellery, carpets, ceramics, spices, and leather. The bazaar also has up to 22 gates leading into different sections. Over the centuries, the Grand Bazaar has survived earthquakes and fires, with renovations maintaining its historic character. It remains a symbol of Istanbul’s rich commercial history and vibrant trading culture, reflecting the Ottoman Empire’s reach across three continents.

An entrance to the Nuruosmaniye Mosque. We did not go inside in this trip.

Egyptian Bazaar

The Egyptian Bazaar, also known as the “Spice Bazaar” or “Misir Carsisi” in Istanbul, is one of the oldest and most famous covered markets in the city. It is located in the Eminonou area, directly behind the New Mosque (“Yeni Camii”) and adjacent to the Flower Market. The bazaar was constructed starting in 1660 and completed around 1664, funded by revenues from the Ottoman province of Egypt, which is how it got its name. The flower market had all sorts of plant and vegetable seeds for planting. We also saw some very cute onions, the size of small bouncing balls. My wife commented that Turkish cuisine doesn’t use much onions, unlike south Asian dishes.

Originally, the bazaar was intended to provide financial support for the upkeep of the New Mosque complex and quickly became the city’s primary spice market. It is built in an L-shape with 113 shops and was historically a centre for herbalists and cotton dealers. The market was also used as a madrasa before being converted into a bazaar.

The Spice Bazaar is famous for its wide variety of products including spices, nuts, dried fruits, herbs, Turkish delights, cheeses, greengrocers, flower markets, and fish stores, dried meats like pastirma and sujuk, as well as snacks, handcrafts, and jewellery. It is a brilliantly colourful sight and shopping experience.

Suleymaniye Mosque

The Suleymaniye Mosque is one of Istanbul’s largest and most important mosques, commissioned by Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent (also called “Qanuni Sultan” – for the legal reforms he instituted and considered to be a righteous leader), designed by the great Mimar Sinan. Construction began in 1550 and was completed in 1557-1558, well before the death of Suleyman in 1566 at the age of 71, after 46 years of rule, making him the longest reigning sultan in Ottoman history. Suleyman inherited the throne from his father (Selim I) in 1520. During his time he conquered Belgrade, Rhodes, Moldova and a large part of Hungary. He laid siege to Vienna in 1529 but the military push failed for various reasons. Fighting Safavids in the east, Suleyman conquered a large part of the middle East, extending from Algeria in Africa. Many historians considered this period as the peak of Ottoman rule. However, by the end of his reign, the vast Ottoman Empire faced mounting challenges in governance and control. Competing and increasingly sophisticated ideas from the European Renaissance, technological advancement, and escalating debt from years of military expansion all placed immense strain on the empire’s stability and resources.

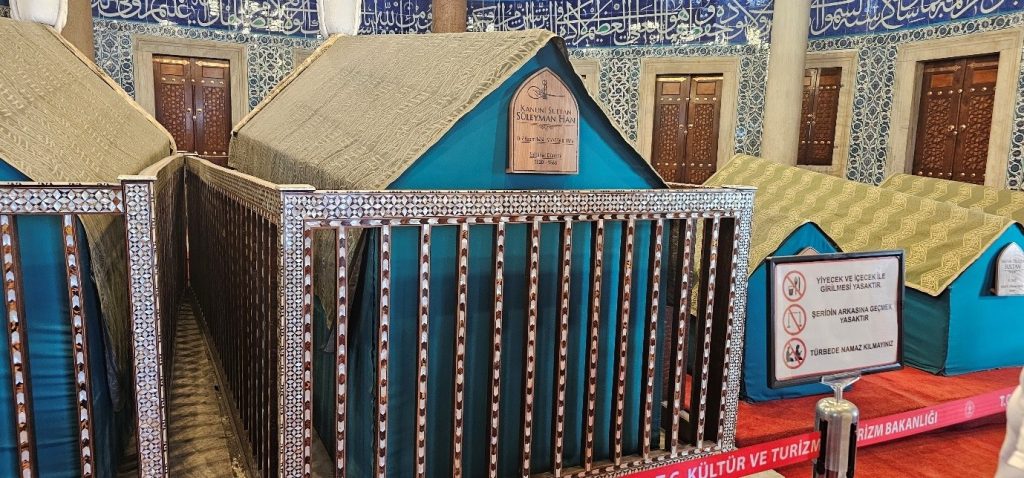

The mosque is situated on Istanbul’s “Third Hill” and offers spectacular views over the city and the Golden Horn. It is renowned as a masterpiece of Ottoman architecture, featuring a large central dome, smaller domes, and four slender minarets. Sultan Suleyman is buried here, together with his wife, Roxelena.

Beyond being a mosque, it was part of a larger complex called a “kulliye”, which included a hospital, soup kitchen, schools, a bathhouse, and other charitable institutions that catered to the needy of the city regardless of religion. Both Sultan Suleyman and his wife Roxelena, as well as Mimar Sinan are buried within the complex.

Over time the mosque has been restored multiple times from damage from fires and earthquakes. In our last visit, for example, there was some significant restoration work carried out which prevented us from taking a look inside. This time there was no restoration work and we prayed Dhuhr in it.

View of the Suleymaniye Mosque from the Bosphorus.

Fatih Mosque

The Sultan Fatih Mosque (“Fatih Camii”), is a historic mosque in Istanbul commissioned by Sultan Mehmed II, or Mehmed the Conqueror (Fatih Sultan Mehmed). Construction of the mosque began in 1463, about ten years after the conquest of Istanbul, and was completed in 1470. It was built on the site of the Church of the Holy Apostles, an important Byzantine Christian church that also served as the burial place of several Byzantine emperors, including Constantine the Great.

The mosque is part of a large complex (“kulliye”) that includes madrasas (religious schools), a library, a hospital, a dervish inn, a caravanserai, a market, a public kitchen serving the poor, and tombs. It was designed by the Greek architect Atik Sinan (Sinan the Elder), nit to be confused with Mimar Sinan (the greatest Ottoman architect) who came almost a century later.

The current most has been redesigned in the 18th century. It contains the tomb of Mehmed II, whom the Prophet praised.

Galata Tower

The Galata Tower is a historic landmark with origins dating back to the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, who first built a tower in that area around 507-508 AD. The current tower was rebuilt by the Genoese in 1348-1349 as part of their fortified colony in Galata, and it was originally called the “Tower of Christ.” The tower has served multiple purposes over centuries, including a lighthouse, prison, observatory, and fire watchtower, following the conquest of Constantinople. It stands around 62 meters tall and offers panoramic views over Istanbul, making it a very lively and bustling tourist attraction. For time constraint we did not go up the tower, but enjoyed its surroundings. Nearby there a is Salt Bey restaurant where we ate lunch.

Arasta Bazaar

Arasta Bazaar is a historic and charming marketplace located in the Sultanahmet area, right behind the Blue Mosque. Built in the 17th century during the reign of Sultan Ahmed I, it was originally intended to generate revenue for maintaining the Blue Mosque complex. The bazaar is known for its classic Ottoman architecture with a narrow street lined by small shops topped with domes, creating a picturesque setting.

Unlike the more crowded Grand Bazaar, Arasta Bazaar offers a more intimate and relaxed shopping experience, with around 70 shops selling traditional Turkish goods such as carpets, ceramics, textiles, jewellery, spices, and souvenirs. It also houses the Mosaic Museum, featuring stunning Byzantine mosaics discovered nearby, adding a rich historical aspect to the visit. The bazaar was initially known as the “Sipahiler Carsisi,” serving as a marketplace for Ottoman cavalry soldiers to buy military supplies, but it has evolved over the centuries into a popular destination for authentic Turkish crafts and culture. There is also free Whirling Dervish dancing that can be seen in a café at the end Hagia Sophia end of Arasta Bazaar.

New Mosque

The New Mosque (or “Yeni Camii”) is located in the Eminonou near the southern end of the Galata Bridge. Its construction began in 1597 under the commission of Safiye Sultan, wife of Sultan Murad III, but was delayed for decades due to political and financial challenges. The project was finally completed in 1663 under Turhan Sultan, the powerful wife of Sultan Ibrahim and mother of Sultan Mehmed IV.

Architecturally, the mosque is a masterpiece of classical Ottoman style with a cascading arrangement of 66 domes and semi-domes and two slender minarets. The large central dome measures about 36 meters in height. Its design draws inspiration from earlier Ottoman mosques, including works by Mimar Sinan and Sedefkar Mehmed Agha. The mosque complex (“kulliye”) originally included a hospital, school, palace, and the famous Spice Bazaar, which remains a bustling marketplace today.

Eminonou Pier

Eminonou Pier is a very lively and historic ferry terminal located along the Golden Horn waterfront in the heart of the Eminonou area. It serves as a major transportation hub connecting the European side of Istanbul to various destinations, including the Asian side, the Princes’ Islands, and scenic Bosphorus cruises. The pier offers stunning views of the Bosphorus and is surrounded by iconic landmarks such as the New Mosque (Yeni Camii) and the Spice Bazaar. Nera the pier is also the Galata Bridge, which is notable for its two-level structure: the upper level accommodates vehicle and pedestrian traffic – which we walked on, while the lower level houses restaurants and cafes.

The area around Eminonou Pier is bustling with activity (which area of Istanbul isn’t?), featuring cafes, street food vendors, and vibrant markets. It is a popular spot for both locals and tourists who come to enjoy ferry rides, explore Istanbul’s maritime history, and take in panoramic views of the cityscape including the nearby Galata Tower, and stunning view of The New Mosque.

Besiktas Stadium

We explored the Besiktas stadium area including the club shop.

The Besiktas ferry port, where we took a ferry ride from to Besiktas and Buyukada.

One of the gates of the Dolmabache Palace. We did not go inside, to keep the trip light on museums.

Hammams

Hammams, or Turkish baths, have been an integral part of Istanbul’s cultural and social life for centuries, blending architecture, tradition, and physical and mental well being. Originating from Roman and Byzantine bathing customs (which is why we have Roman baths in Bath), Istanbul’s hammams evolved during the Ottoman era into ceremonial spaces for cleansing, relaxation, and socialising. Hammams generally consist of a series of rooms ranging from cooler changing areas, warming rooms, to hot steam rooms with marble platforms for scrubbing and washing, combining architectural beauty with a ritual cleansing experience. I am not a fan of the Turkish hammam experience! Today, reportedly around 60 of the original 237 hammams in Istanbul remain in operation, some as luxury wellness destinations. We saw a few dotted around Istanbul’s old city.

Cagaloglu Hammam (built in 1741): The last large Ottoman public bath constructed in Istanbul, known for its magnificent marble interiors and traditional bathing rituals. It also hosted bridal baths during the Ottoman period. Aga Hamami is one of the oldest Turkish baths in Istanbul, built in 1454 shortly after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople. Like all the hammams, they have undergone restoration over the centuries, and remain a cultural landmark and experience showcasing Ottoman bath architecture and social customs from the 15th century onwards.

Suleymaniye Hammam (circa 1557) is part of the Suleymaniye Mosque complex. This hammam was frequently used by sultans and features classic Ottoman architectural elements like domes and marble inlay. There are others like Gedikkapi Hammam (built in 1475), which is located near the Grand Bazaar. Another of the older Hammams is Kilic Ali Pasha Hammam (1580), which was commissioned by the Ottoman admiral Kilic Ali Pasha and designed by the architect Mimar Sinan.

Taksim Square

Taksim Square, located in the Beyoglu area of Istanbul, is a major cultural and social hub often considered the heart of modern Istanbul. The name “Taksim” means “division” or “distribution” in Turkish, referring to its historic role as a water distribution point during the Ottoman era. Today, it serves as a bustling public square surrounded by prominent landmarks such as the Republic Monument, which commemorates the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923.

The square is a focal point for transportation, shopping, dining, and entertainment, with major shopping streets like Istiklal Street beginning at its edge. It is flanked by important buildings including the Ataturk Cultural Center, Taksim Mosque, and Gezi Park, the latter of which gained international attention during the 2013 protests against urban development plans. Taksim Square is known to be a vibrant gathering place for political demonstrations, public celebrations, and cultural events. While didn’t see much of that, the area was busy and vibrant. During the most recent coup attempt in Turkiye on the night of July 15-16, 2016, soldiers occupied Taksim Square as part of their efforts to take control of the city. Around midnight, reports indicated that soldiers were inside Taksim Square, where they tried to assert control. However, large crowds of civilians and police gathered to oppose the coup forces, and by the early hours of July 16, around 30 soldiers surrendered to police in Taksim Square. At the time my in-laws were staying in Taksim Square for their holiday, but they did not see any impact.

There are a few authentic Pakistani restaurants very close by where we ate a few times.

Istiklal Street

Istiklal Street (“Istiklal Caddesi”) is one of Istanbul’s most famous and vibrant pedestrian shopping streets. It is like London’s Oxford Street though smaller and narrower. It stretches about 1.4 km from Taksim Square on one end to the Galata Tower on the other.

The street has a rich history dating back to the Byzantine era when the area was known as Pera (which it still is) and was home to Genoese and Venetian traders. It became a prominent commercial and cultural centre and was renamed Istiklal, meaning “Independence,” after the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923.

There are many fashion brands on Istiklal Street, as well as small shopping malls with smaller shops. The street is also renowned for plenty of interesting architecture, featuring a mix of late Ottoman, neoclassical, and modern styles. It is home to historic landmarks like St. Antoine Church, which seems to be quite heavy guarded. There is also nostalgic red tram that runs along the street, with tourists often posing for pictures.

Taksim Square Mosque

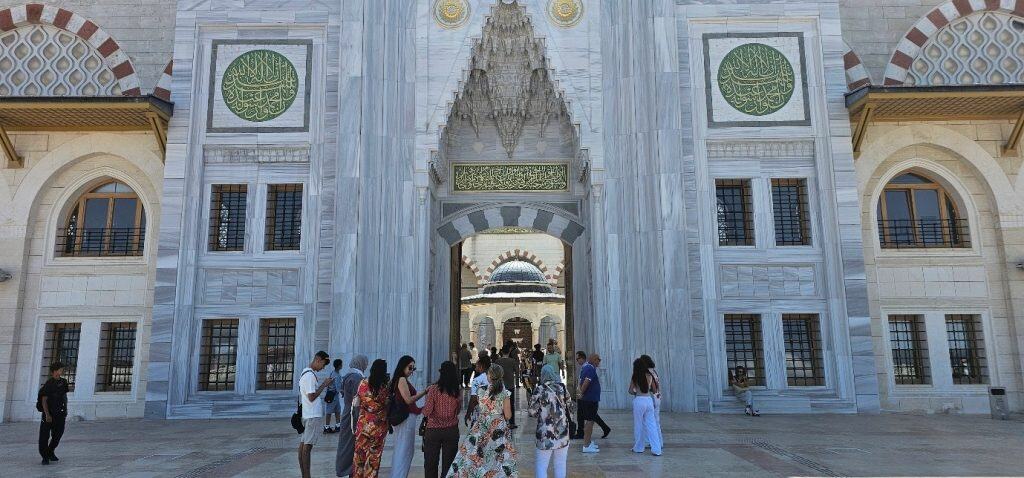

Taksim Mosque (“Taksim Camii”) is a modern mosque located in the heart of Taksim Square. The idea to build a mosque in Taksim dates back over 150 years, but its construction faced political and legal challenges for decades, partly because Taksim Square was long associated with secularism and republicanism. The project gained momentum in the 2010s and construction officially began in 2017.

The mosque was completed and inaugurated on May 28, 2021. It combines Ottoman and contemporary architectural elements and has a capacity for about 3,000 worshippers. The mosque looks far bigger than it is, partly because it is near the open space of Taksim square making it stand out and seem larger. It is part of a larger complex that includes an underground parking area, library, exhibition hall, event space, and a soup kitchen.

Night view directly as you step outside Taksim Square Mosque.

Princes Islands – Buyukada

We spend the best part of a day in Buyukada, which is the largest of The Princes’ Islands, located off the coast of Istanbul in the Sea of Marmara. We took the ferry from Eminonou, which meant we got to see the sites of Istanbul from the Bosphorus without having to take a “Bosphorus cruise.” The journey was very pleasant, taking about 45 minutes. The Princes’ Island’s date back to Byzantine times when they were used as places of exile for royalty and political prisoners, which gave rise to their name “Princes’ Islands.” Today, Buyukada is a popular summer retreat for Istanbul residents and tourists seeking to escape the city’s hustle. You enter the island from its bustling port area. In the island, all petrol powered motor vehicles are banned. Instead there are small battery powered vehicles, including what looked like golf-buggy like vehicles, carts, bicycles, small battery-powered scooters and e-bikes are plentiful. The island is hilly, green, very clean and overall extremely tranquil. There were also a few horse-drawn carriages.

We visited the Hamidiye Mosque, which was built between 1893 and 1895 by the order of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Architecturally, it reflects the Late Ottoman style, blending traditional Islamic design with European influences, which is evident in its elegant minaret, domed roof, and European internal decorations. The island is renowned for its beautiful Ottoman-era wooden mansions scattered across the island. It was very easy to walk around the island, and we probably covered half the island by just walking around. The food is also very good, though not any different from Istanbul.

The trip to Buyukada via ferry from Eminonou Pier is exquisite. You get to see so much of both European and Asian sides of Istanbul from starting out from the Bosphorus and then the Sea of Marmara.

View of Istanbul mainland from Buyukada.

Buyukada is full of beautifully designed churches.

IDO ferry port at Yenikapi

The IDO (“Istanbul Deniz Otobusleri”) ferry port at Yenikapi is Istanbul’s largest and busiest ferry terminal, located on the Marmara Sea coast in the Sultanahmet area. From here, fast ferries and seabus catamarans operate routes to multiple destinations, including coastal areas, Marmara Sea islands, and cities across the Sea of Marmara such as Bursa, Bandirma, Yalova, and others. We travelled from Yenikapi to Mudanya en route to Bursa via ferry, which was around 2 hours long. The ferry ride was very comfortable.

Ulu Camii

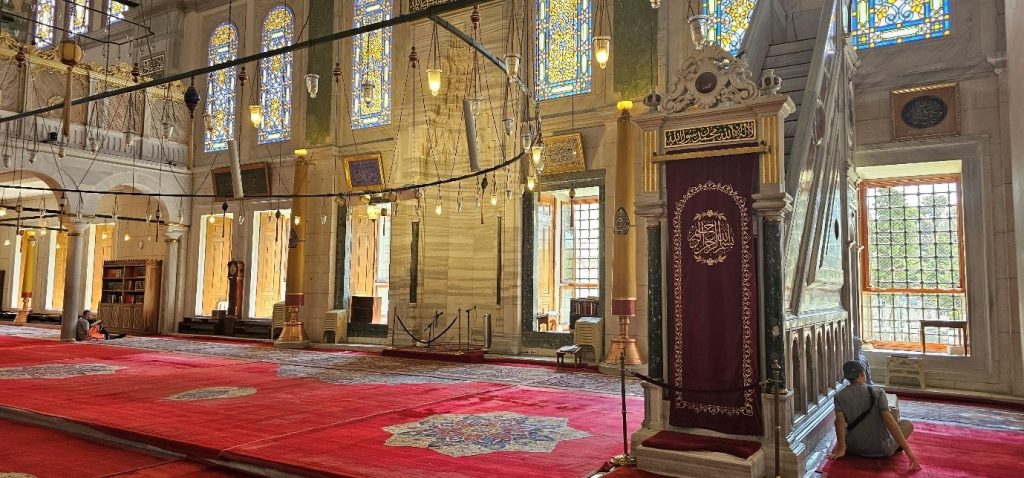

The Ulu Camii, or the Great Mosque of Bursa, is a historic and architecturally significant mosque located in Bursa, the first capital of the Ottoman Empire. Commissioned by Sultan Bayezid I, it was constructed between 1396 and 1399 as a symbol of Ottoman power and spiritual prominence following his victory at the Battle of Nicopolis. The mosque is situated just opposite the historic Koza Han Bazaar in Bursa.

One of the mosque’s most distinctive features is its roof, which has 20 domes arranged in four rows and supported by 12 massive columns, creating a spacious and impressive interior. This multi-domed design was revolutionary for its time and influenced later Ottoman mosque architecture. The mosque’s prayer hall offers a peaceful, contemplative atmosphere with what looked like a forest of large columns and expansive arches.

The mosque also houses a beautiful inner ablution fountain (“sadirvan”) with a skylight that softly illuminates the space. Inside, we admired the extensive collection of large calligraphy panels, the wooden minbar and the general ambiance of the place with quite unique Arabic calligraphy written in black ink on cream walls. The only other place I recall seeing this style was the great mosque of Edirne.

The minarets of Ulu Camii can be seen approaching the site. Next to it is the historic bazaar.

Extraordinary calligraphy on the walls of the Ulu Camii. When you see it for the first time you are mesmerised by the beauty of the designs all around the inside walls of the mosque. I have never seen anything like this, and the serene atmosphere it creates.

Inside the historic market near Ulu Camii, the Koza Han and Kapali Carsi area.

Bursa Citadel

Bursa Citadel is the oldest part of Bursa and served as the original fortified settlement of the city. The first city walls were built by the Bithynians around 202 BC and were later modified and expanded by the Romans, Byzantines, and Ottomans. When the Ottomans conquered Bursa in 1326, the citadel housed the entire city within its walls, which stretched for about two kilometres and included 67 towers and five main gates.

The citadel area features narrow streets with historic Ottoman houses, many of which have been converted into restaurants, shops, or boutique hotels today. The citadel provides stunning views of Bursa, though only some parts of the original wall remains.

Inside the citadel area are the tombs of Osman Gazi and Orhan Gazi. The citadel offers a glimpse into Bursa’s early history as the first Ottoman capital and serves as a cultural and historical hub with museums, restored structures, and charming streets.

Tophane Clock Tower

The Tophane Clock Tower in Bursa is a historic landmark built in 1905 during the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II – the last Ottoman sultan. Standing 33 meters tall with six floors, the tower exemplifies Ottoman architecture with a neoclassical style, featuring a square base, elegant arches, and clock faces on all four sides. Originally, it served both as a clock tower and a fire lookout, providing panoramic views of Bursa from its elevated position in Tophane Park.

It is locate near the tombs of Osman Gazi and Orhan Gazi. Nearby, the area offers cafes and gardens, making it a popular spot for both sightseeing and relaxation. The tower also has a unique feature of four cannons used historically to signal the hour of sunset during Ramadan. The use of cannon fire as a time marker was common throughout the Ottoman Empire before the widespread mechanical clock use.

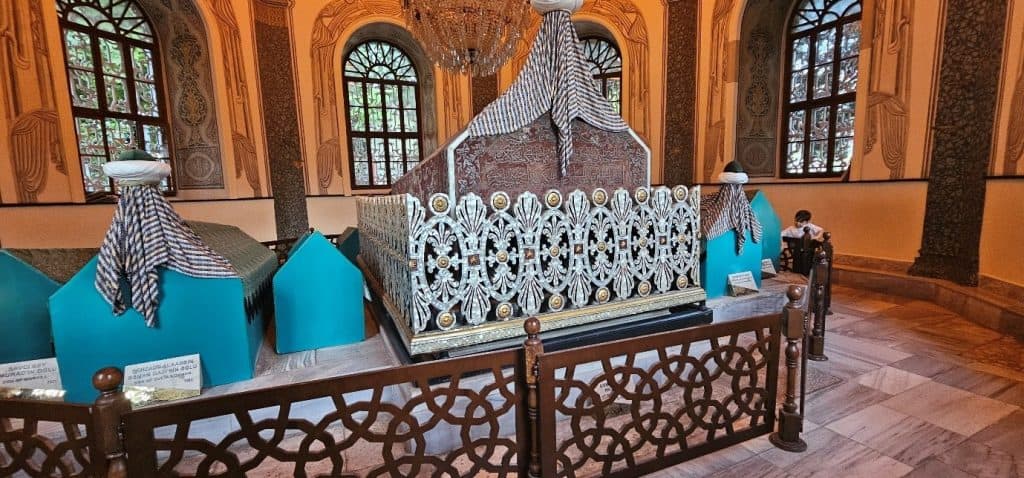

Tombs of Osman Gazi and Orhan Gazi

The Tombs of Osman Gazi and Orhan Gazi are located in the Tophane area of Bursa. Osman Gazi, the founder of the Ottoman Empire, and his son Orhan Gazi, who expanded the empire and conquered Bursa as its first Ottoman capital, are both buried here. It is a special site of historical significance.

The exact timing of Osman’s death is uncertain, but most historians agree he died before or around the capture of Bursa in 1326. Some sources, including Ottoman tradition, claim Osman lived just long enough to hear of Bursa’s conquest by his son Orhan and died shortly after. However, many contemporary scholars believe his death likely occurred in 1323 or 1324, before the final conquest. The confusion stems from sparse records and later chronicles, which often mix legend and fact. The majority consensus is that Osman died near the siege’s end rather than witnessing the victory himself.

Osman’s tomb could have been moved to Bursa after its capture. Osman I expressed his wish to be buried in Bursa, so after the city was conquered by his son Orhan, his remains were transferred to Bursa and laid to rest there.

The tombs rest in a structure called “Gumuslu Kubbe” (“the Silver Dome”), which was built on the site of a Byzantine chapel known as the St. Elias Monastery dating back to the 11th century. The original tomb buildings suffered major damage from a fire in 1801 and the devastating earthquake of 1855, leading to their reconstruction in the mid-19th century. Osman Gazi’s tomb is octagonal and decorated with mother-of-pearl inlaid wooden sarcophagi, while Orhan Gazi’s mausoleum displays 19th century Turkish Baroque ornamentation. The tomb complex also contains the remains of several members of the Ottoman dynasty, including Orhan’s wife Asporca Hatun and other relatives. I should say for clarity, in Ottoman burial practice, even for significant figures like Osman Gazi and Orhan Gazi, the body was not placed inside the sarcophagus itself. The actual body was buried directly in the ground underneath or within a burial chamber beneath the sarcophagus, in keeping with Islamic practice of ground burial.

The gates into the citadel area with the two structures for the the tombs of Osman Gazi and Orhan Gazi. As you go past the tombs, the space opens up into the stunning open area from where the sprawling city of Bursa can be viewed.

Green Mosque

The Green Mosque (“Yesil Camii”) in Bursa was commissioned by Sultan Mehmed I and built between 1412 and 1419, during his reign to reunify the Ottoman Empire after a period of civil war among Bayezid I’s sons. Skilled craftsmen from Tabriz, Iran, were used to decorate the mosque’s intricate tile work, elegant calligraphy, and architectural design. The complex also includes the royal Green Tomb for Mehmed I and his family which is just opposite the mosque itself (last picture below), completed shortly after the mosque. The building has undergone restorations following various earthquakes. It’s has a very calming atmosphere and during the Maghrib that we were there, there was an event for children at the front of the mosque which looked very cute.

The Greem Tomb where Mehmed I is buried.

Uludag

In our visit to Bursa we took a cable car ride known as the “Bursa Teleferik” from Teferruc station of around 22 minutes to get to Uludag (“Great Mountain”), which is the highest peak in the Marmara region, reaching a height of 2,543 meters (8,343 feet). It is the longest cable car line in Turkiye, covering a distance of about 9 km (5.6 miles). The ride includes three stations: Teferruc (the base station in Bursa city), Sarialan (a mid-station with walking trails and teahouses), and the final stop where the hotels are located on Uludag. We found the ride truly breathtaking. The cabins seat up to eight people, and despite the outside temperature and direct sunlight, their aerodynamic design somehow kept us refreshingly cool throughout the journey. Large panoramic windows provided stunning 360-degree views of lush, dense forests, rugged mountains, and the sprawling cityscape of Bursa below.

Uludag is renowned as a major national park and one of Turkiye’s premier winter sports centres, attracting thousands of visitors for skiing, snowboarding, and other winter activities. Visiting in summer we didn’t see any of that, but we did see many families preparing to board with camping gear and picnic baskets.

The Teferruc base station in Bursa city, where day trippers like us are getting ready to board around 11am when it opens.

New Thermal Baths

Yeni Kaplica, or the “New Thermal Baths,” in Bursa was built in 1552 by Rustem Pasha, the Grand Vizier to Sultan Suleyman. Although called “new,” the baths are centuries old and represent classic Ottoman bath architecture, possibly designed by Mimar Sinan or his students. On our visit there, we wanted to go to the “Old Kaplica” or “Eski Kaplica” and despite sensing that the driver might miss hearing and take us to the Yeni Kaplica (New Thermal Baths), because the Eski Kaplica is not as well known, that is exactly what happened, which was a bit annoying. The Old Kaplica is older and dates back to the 14th century, which unfortunately we did not get to see.

The baths use thermal mineral water sourced from nearby springs and feature multiple domes, spacious hot pools, and traditional bath halls. The men’s section retains much of its original opulence, offering visitors an authentic experience of Ottoman-era bathing culture. Unlike the Eski Kaplica (Old Thermal Baths), which dates back earlier and is smaller, Yeni Kaplica is larger and was constructed to accommodate more visitors.

This historic spa continues to operate today as a popular destination for relaxation and therapeutic bathing, blending centuries-old tradition with functional modern use.

Tomb of Ertugrul Gazi and others

The Tomb of Ertugrul Gazi in Sogut is a significant historical and, for many people spiritual landmark marking the resting place of Ertugrul Gazi. It’s reported that the tomb was originally built as a simple open tomb by Osman I in the 13th century and was later converted into a mausoleum under Sultan Mehmet I in the 15th century (1402-1421). The current structure, with its distinctive hexagonal shape and dome, was constructed during the late 19th century under the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II.

The tomb is located within a larger cemetery that also includes the graves of important Ottoman figures such as Ertugrul’s wife Halime Hatun, his younger brother Dundar Bey, and his son Samsa Alp. Nearby are honorary graves for other notable figures like Turgut Alp, who as Ertugrul fans would know, was a close companion and warrior of Ertugrul. But many of the graves are honorary to serve a symbolic purpose rather than marking the actual burial sites of those figures. For example, Turgut Alp’s actual grave is reported to be in Inegol, which is an hour from Sogut.

There are two guards outside Ertugrul’s tomb. When we got there, around midday, they performed a ceremonial changing of the guard, which was much loved by all the visitors at the time. We almost missed it as we did not expect there would be a ceremony.

The trouble with visiting these graves is that it often brings to mind the vivid images of the film characters, which can be distracting; so it’s important to set those aside and focus solely on the names during your ziyarah prayers. But, I’m sure my children prayed for the characters alive today!

Holes in the window shutters date back to 1921, when Greek soldiers who had occupied Sogut shot at the structure housing Ertugrul’s grave.

View looking back at the tomb structure of Ertugrul Gazi.

The Sogut Ethnographical Museum, which displays life-size statues of Ottoman sultans, close to the tomb of Ertugrul Gazi.

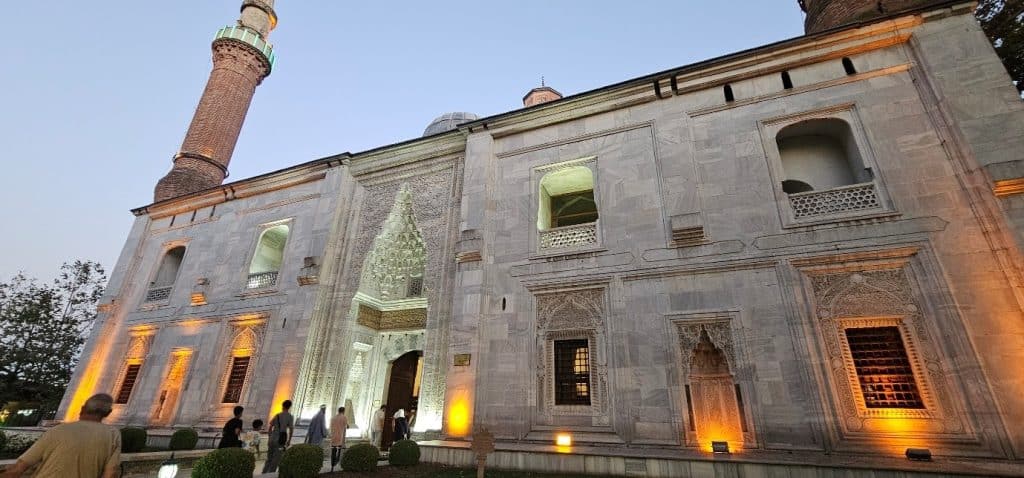

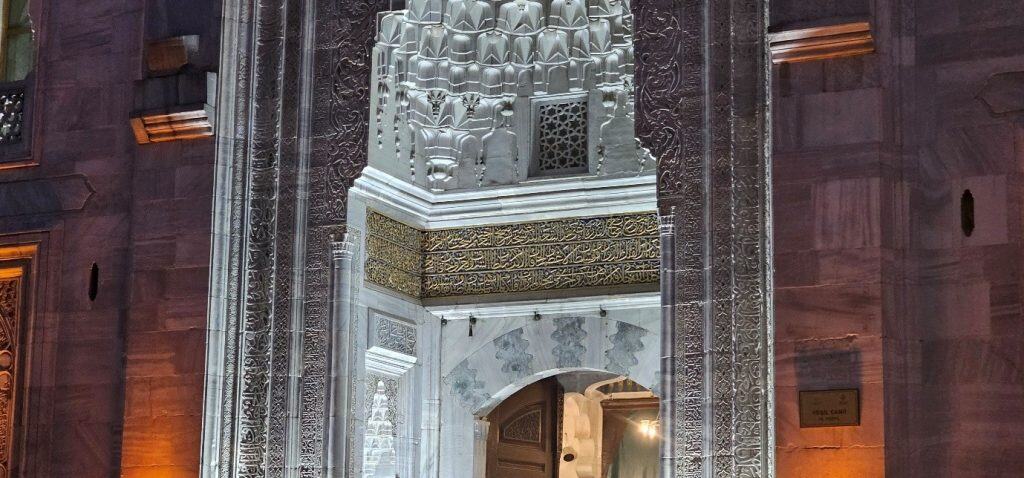

Ertugrul Gazi Mosque

The Ertugrul Gazi Mosque in Sogut, holds great historical and symbolic significance as one of the earliest Ottoman religious sites. It was originally built in the 13th century by Ertugrul Gazi. Often called the “Masjid with a Well,” it was erected to serve the spiritual needs of Ertugrul’s tribe upon settling in Sogut, which marked the beginning of the Ottoman presence in the region. Today this mosque has been expanded and fully restored, including use of stone and wood reflecting the simplicity of 13th century heritage as a tribal mosque.

Hanli Bazaar

Anyone who has watched Ertugrul would be familiar with Hanli Bazaar. It became the main commercial centre following the capture of Sogut during Ertugrul’s time. The current Hanli Bazaar in Sogut is not exactly in the same physical location as the original historic market from Ertugrul’s era. The original Hanli Bazaar was situated near the strategic trading routes and caravanserais, which are much further west and south. The modern bazaar, which was built in the early 1900s, has been deliberately positioned within the town centre of Sogut to reflect the spirit of the historic marketplace while serving today’s visitors to the Ertugrul Gazi sites. None of the original structures of Hanli Bazaar remain today. However, we found the design of today’s Hanli Bazaar to still evoke the sense of history and culture that the historic Hanli Bazaar would have had during the early Ottoman period.

Restaurant near Hanli Bazar in Sogut where we ate lunch after travelling from Bursa.

Solar Beach & Black Sea swimming

We choose to visit the Solar Beach which by sheer luck had very few people around on the day of our visit, which allowed us to enjoy stunning views.

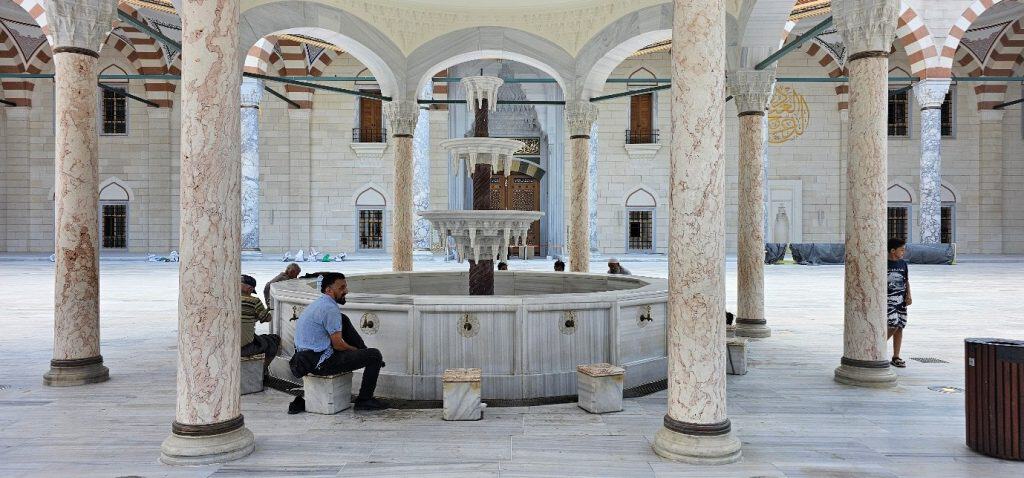

Camlica Mosque

The Camlica Mosque (“Camlica Camii”), located on Camlica Hill in Istanbul’s Uskudar area on the Asia side, is Turkiye’s largest mosque and a stunning symbol of Islamic architecture completed in 2019. It can accommodate up to 63,000 worshippers and features six soaring minarets, multiple domes with the main dome standing 72 meters high. It is so big that it can be see from miles away on the European side of Istanbul. The carpet is of such high quality and has unique blue shade and patterns that I have not seen anywhere in the world. It is more elegant and architecturally interesting than the great mosque of Casablanca. Extraordinary. Being on a hill, the mosque offers spectacular panoramic views of Istanbul and the Bosphorus – some of the view you can see in the pictures below. The design of the mosque and the architectural detail is truly breathtaking. For example, the carpet in the mosque is unlike anything I have seen anywhere else in the world, which adds the mosque’s grandeur and spiritual ambiance. We could easily have spent the whole day in the mosque.

Designed by two female architects, Bahar Mizrak and Hayriye Gul Totu, the mosque complex includes a museum of Islamic civilization, a garden, an art gallery, a library, a conference hall, and underground parking for up to 3,500 vehicles. It even has childcare facilities and elevators designed for easy access and inclusivity.

The central wudu fountain structure reminded me of the Amr ibn al-‘As mosque in Cairo, where there is a similar structure that, at least based on my memory, looks almost identical from afar.

Akasya shopping mall

Akasya Shopping Mall, located in the Acibadem neighbourhood of Istanbul’s Asian side, is a premier destination for shopping, dining, and entertainment. It houses hundreds of local and international brand stores, a large cinema complex including IMAX, and KidZania Istanbul. The mall also has a very good selection of food. It wasn’t crowded when we went. The shopping mall is just a short 10-15 mins travel on taxi ride further south on the Asia side of Istanbul from Camlica Mosque.

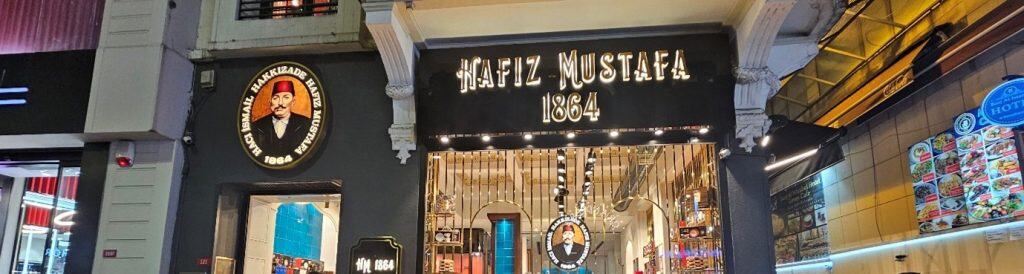

Sweets shops: Hafiz Mustafa, Ali Muhiddin Haci Bekir

Istanbul has many very famous sweets shops. Among the most famous is probably Hafız Mustafa 1864, which was founded by a confectioner who began selling sweets near the Fatih Mosque and whose name remains synonymous with traditional desserts today. They have also expanded in Dubai and London. There is also Ali Muhiddin Haci Bekir, which was founded earlier in 1777, which is still operating. There are others, too, but these two were quite prominent on Istiklal Street.

Eyup Sultan Mosque

The Eyup Sultan Mosque is one of Istanbul’s most historically significant and sacred mosques. Commissioned by Sultan Mehmed II (“Fatih Sultan Mehmed”) in 1458, it was built near the Golden Horn on the site believed to be the burial place of Abu Ayyub al-Ansari (Turkish people colloquially refer to him as “Eyup Sultan”). Eyup Sultan Mosque is also linked historically to Ottoman sultans’ coronation ceremonies, where new rulers would come here for religious blessing marking their accession. It remains a vibrant religious, cultural, and historic landmark today.

Many other companions are claimed to be buried in Istanbul, including Abu Darr al-Ghifari (one of the “Ashab al-Suffah” – “The People of the Bench” who lived and devoted their lives to study and teaching in the Prophet’s mosque). None of these claims can be verified with certainty. The most reliably documented site is the grave of Ayyub al-Ansari, although even this claim may not withstand rigorous historical scrutiny (e.g. as we have in hadith classification). Nevertheless, during a chance conversation with a tour guide who approached me spontaneously, he earnestly tried to persuade me that there were other Companions of the Prophet Muhammad buried in the Istanbul.

Reportedly a fragment of the Prophet’s hair kept in a glass casket. The mosque also claims to house a plate of the Prophet, and his foot print. None of the relics are verifiable objectively, with no well-documented chain of transmission, and there are plenty of reasons to doubt such claims.

Eyup-Pierr Loti cable car

The Eyup-Pierr Loti Cable Car ride probably offers one of the most exquisite view of any city anywhere in the word. The views are truly breath-taking. It pales our Docklands cable car ride into insignificance. The cable car line acts as a lift connecting the historic Eyup area with the Pierre Loti Hill. We went on the ride after our visit to Eyup Sultan Mosque. But you don’t have much time. The cable car ride lasts just under 3 minutes, covering a distance of approximately 384 meters (about 1,260 feet). My children commented “is that it” expecting a much longer ride similar to the Teleferric journey to Uludag in Bursa. The ride ascends over the Eyup Cemetery and provides stunning views of the Golden Horn. At the top, we arrived near the Pierre Loti Cafe, a famous spot named after the French novelist Pierre Loti who loved this tranquil hill for its panoramic views over Istanbul.

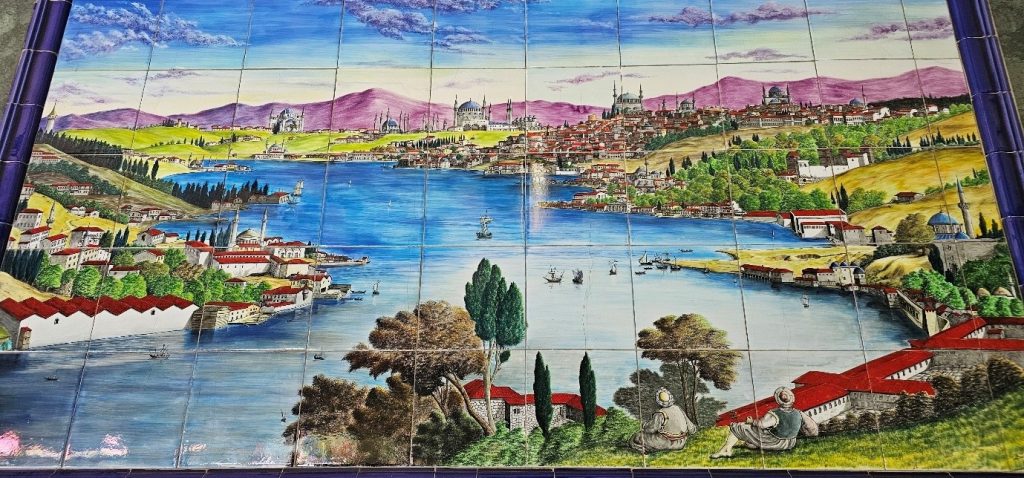

A painting of the Pierre-Loti Hill view which was on display at the cable car station. The contrast with the picture I took shows the development of Istanbul since the painting.

Balat – coloured steps and houses

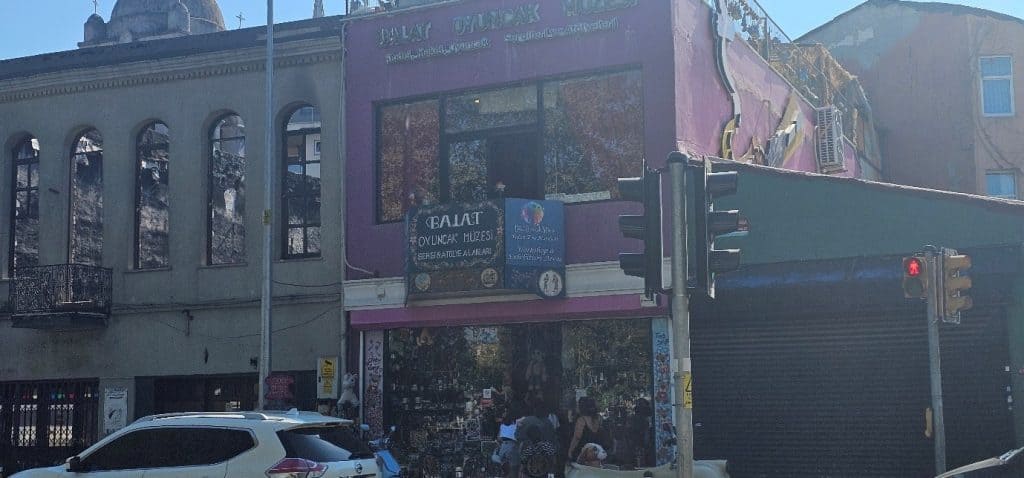

Balat is a lively walking area in Istanbul brimming with charm and history. We visited its most iconic feature, the famous rainbow-painted wooden houses that line the narrow, cobblestone streets, especially along Kiremit Street. Many of these houses date back 50 to 200 years. It also has steep cobbled streets adorned with colourful steps and popular local cafes. There is also a charming coloured umbrella display located in the courtyard of Dimitrie Cantemir Museum Cafe. There are many things to charm one in Balat, including an old toy museum and with cars not so apparent the area is a lot quieter than other parts of Istanbul. This peaceful vibe makes wandering the streets even more enjoyable, allowing one to truly soak in the nostalgic and historic ambiance of the area.

Sekullu Mehmat Pasha grave

A label beside the entrance provides the following description (presented here unedited).

“One the most notable names of the classical age of the Ottoman Empire, Sokullu Mehmed Pasha has served Kanuni Sultan Suleyman, Selim II and Murat III as the grand vizier. Mehmet Pasha who was of Serbian origin was conscripted as part of the devchirmeh system (conscription of Christians with the purpose of joining the janissaries [the Ottoman army] of the Ottoman Corps) in 1519 and had converted to a Muslim before he was educated and sent to Istanbul. In 1541, he had been employed as the chief warder then charged as the Captain of the Sea in 1546, following the death of Barbaros Hayrettin Pasha. He became grand vizier in 1565 and has served for fourteen years, three months and seventeen days, which made him the longest serving vizier.

The Turbe [tomb/resting place] if part of a complex consisting of a madrasah darulkurra (school of Koram reciters) and a fountain. The turbe and been built by Mimar Sinan for Pasha’s purely died children and Pasha himself was buries here whe he was killed in 1579. The interior of the turbe was planned hexadecagonal while the external structure was octagonal planned. It was constructed of limestone and was covered with a dome, The lightening was planned on a two lined window system where the bottom row windows are of marble frame and metal grilled and the top row ones are pointed and plaster grills. Verse-e-Kursi was written in white Thuluth calligraphy on dark blue ground at the tiles surrounding the top row windows on the turbe. Sarcophaguss belonging to Sokullu Mehmed Pasha and his family members exist in the turbe.”

There is also a Sokullu Mehmed Psha mosque which we visited in our last trip and met the orphan children who studied there.

Food

Delicious Bengali food ordered from a local restaurant.