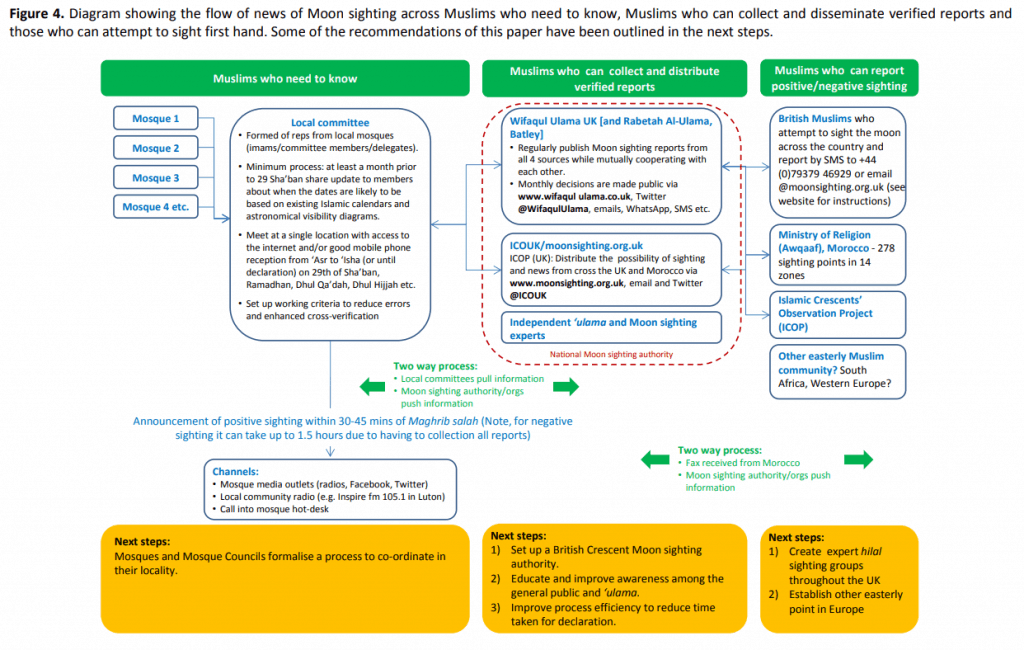

It’s now almost six years since my study unpicking an issue in Muslim communities and working with key stakeholders to produce a strategy for unifying Crescent moonsighting in the UK (see summary diagram below). Since then, the UK’s moonsighting process has got slicker, and there are more regular “sighters” covering a greater breadth of the UK. These were some of the recommendations of the study and ideas that stakeholders were thinking about.

However, while the process capability has indeed improved, the core problem itself has remained as intractable as ever. That is, we’re no closer to any sense of consensus and alignment between those preferring local (to be read as scientifically verifiable crescent moon sighting in the UK) versus global sighting (to be read as “fixed to Saudi declaration” which is invariably linked to the birth of the moon or the Umm al-Qura calendar).

In the last six years, for example, of the 11 Eid’s, five have been celebrated on different days, and three (50%) of the Ramadan’s have not started on the same day. Where unity has been evident (which is roughly 50% of the time) it wasn’t necessarily out of a conscious, deliberate effort to ensure a unity of process or brotherly outcome, but by the benefit of that great leveller: chance. When dates on the Umm al-Qura calendar fortuitously lined up with visibility calculations. This rate of alignment has always been there. The challenge has always been to shift this to 100%.

During this time, in 2018 the New Crescent Society was founded by the veteran moon-sighter, Imad Ahmed, which has since done some great work. Producing highly informative viral videos promoting moonsighting and awareness of why the differences in the start and end of Ramadan and Eid persists amongst Muslims in the UK. Moreover, they’ve generated interest in astronomy among many Muslims, particularly through seminars and workshops working in association with the Greenwich Royal Observatory. They’ve also organised what is quite possibly the largest symposium of imams, mosque leaders and scholars from a variety of backgrounds to explore how to solve the problem of crescent moonsighting in the UK. Most recently, they had Facebook supporting them by live streaming Shawwal 1442 moonsighting on their page. In short, the efforts of the New Crescent Society have been ground-breaking and educational. To his credit, Imad has shot up into the premier league of influential British Muslims.

However, whilst all of this is highly commendable, what has now surfaced in the most recent Eid al-Fitr (2021) is a new fracture directly created by the New Crescent Society which has made me question their approach.

So, what’s happened?

“Traditionally-local” moon sighters did not see the crescent in the UK on Tuesday 11th May in line with visibility calculations and as per process accepted the report of verified sighting from Morocco (where it was possible to see the youngest crescent), and declared Eid for Thursday 13th May. It meant that they aligned with the Saudi declaration, giving what we call a united or “One Eid” in the UK. However, the New Crescent Society rejected Morocco’s report as applicable to the UK on the basis that moon sighters did not see the crescent anywhere in the geographic territory of the UK on 11 May. As a result, the New Crescent Society didn’t declare Eid al-Fitr for 12th May and rejected the “traditionally-local” sighters position. Instead, the New Crescent Society seem to have virtue signalled their viewpoint of “local,” and grouped all non-UK reports of sightings as “non-local,” levelling Morocco’s system of verified moonsighting with Saudi Arabia’s unverified system. What we had, then, was a narrowed definition of sighting zone that covered only the area of the UK.

In rejecting the sunnah basis of the decision to do Eid on Thursday 13 May, the New Crescent Society seemed to have displayed all the hallmarks of a cult: bullish language, virtue signalling, rejecting consensus, seeing themselves as saviours of the sunnah par excellence etc. whilst fragmenting to less than 1% of Muslims in the UK who may have rejected the overwhelming consensus of Eid al-Fitr 2021. A glance at the comments left on the New Crescent Society’s Facebook page was a reminder of how easily organisations intending to do good can end up unwittingly amplifying confusion and doubt and, in the end, fail to solve much. This trap of “my way or the highway” is an arrogance that has dogged Muslim organisations on moonsighting historically since the 1990s – lessons which I clearly articulated in the 2015 paper.

Here, the New Crescent Society seem to have overlooked the fact that their claim of sunnah-basis of moonsighting for Eid al-Fitr 2021 was no longer sunnah once the wider Shari’ and good judgement considerations such as overwhelming consensus, and public benefit, of a unified “one Eid” on Thursday 13th May became a reality. To insist that it was sunnah despite such context, is, arguably, an unwitting reprehensible innovation in the religion (bid’a).

A new fracture (UK vs regional vs Saudi)?

This new fracture centres around what is meant by “local.” According to the New Crescent Society, it refers to (the political and geographical entity of) the UK. Whereas, according to “traditionally-local” sighters (organisations like Wifaqul Ulama, members of MINAB and other scholars who have been doing moon sighting for decades) it doesn’t mean the UK per se, but a rules-based[1] designated broader sighting zone comprising primarily the UK and Morocco (this is more “regional”). This new fracture brings a playoff between the more narrowed definition of “local” of the New Crescent Society versus the broader definition of the “traditionally-local” moon sighters.

“Local” in the context of moonsighting zone has historically always been somewhat subjective. This has been complicated further under modern nation-state political frameworks, global communication technologies, and the expansion of multi-ethnic societies in the West. The classical Hanafi view, for example, is that sighting doesn’t need to be local with the entire world considered a single sighting zone (matla), unlike the Shafi’ view, and what matters most is accuracy and reliability. The Shafi’ view of local, on paper, is restricted to 48 miles. The Hanafi view, mind you, in practice never materialised and so things were still restricted by geography – this was to be expected because communication wasn’t possible with faraway lands until the advent of modern telecommunications. But what has always materialised in the Hanafi view is the necessity for accuracy/reliability (reducing errors) of sightings. It is indeed on this basis that many of the UK’s Hanafi scholars (the “traditionally-local” sighters) reject Saudi declarations, which are widely known to be inaccurate and unverified; that is, false sightings are reported despite it being scientifically impossible to sight the crescent.

Now, just to make matters a bit more complicated, the Saudi hilal declarations themselves are, arguably, correct according to Saudi law and I would even argue they are compliant to classical Hanbali law which allows solitary reports as admissible for pronouncing the hilal irrespective of whether it is scientifically possible to sight or not. The crucial thing to remember here is that if a Muslim state deems it to be Eid following the day of uncertainty (yaum al-shakk – 29th Ramadan), then, as many hadiths indicate (as well as Islamic law according to Hanbali fiqh), that is as good a declaration of Eid as any. In most Muslim countries today, which do local moonsighting, “local” has come to synonymise with the boundaries of the nation-state. Though I would argue that many counties don’t have a formal well-organised moonsighting setup like there is in Morocco. Some countries like Turkey just go with the calculated birth of the moon and don’t officially do any visibility sightings, even for symbolic reasons. Others like Bangladesh (which has sporadic examples of individuals who look for the new crescent and a central committee) simply follow a formula of adding 1 day to the Umm al-Qura calendar (which always aligns with visibility sightings). Irrespective of the formula they use, the governments of Muslim countries consistently reject differences within their respective countries as they need to set dates, for example, for official public holidays and make provisions for schools to be closed.

However, for Muslim minorities like us in the UK, the discussion of “local” is a bit trickier:

- Muslims in the UK are from diverse ethnicities, lack representational unity, and devolve scholarly authority to local mosques and a plethora of already-existing bodies and educational institutes. This creates an intricate web of loyalties and decision-making that intersects across local, national and international. A good example is Luton. All British Bangladeshi’s in Luton always do Eid and Ramadan together. This is partly because, many Bengali-run mosques are associated with the UK-wide Tablighi movement, which always looks to Saudi for the hilal declaration. For those mosques that aren’t associated with the Tablighi movement (a fair few), it is their shared ethnicity and familial ties with others that compels them to maintain unity. Various arrangements like this are in place for British-Pakistanis (of Barelvi-denominated mosques), -Turkish, -Arab and -Somalis, too.

- Unlike the UK, declaring Ramadan and Eid in Muslim countries involves their judiciary, public bodies or government-level approval and oversight because there are public holidays, planning for large people movements, and provisions for schools and workplaces to be closed etc. In the UK, however, such intense demand isn’t there as a minority population of four or so million people (6% of UK population). The process for sighting remains decentralised and buried within enthusiast cause-related groups and different organisations with different executive authorities. Yet, in Muslim countries, moonsighting has been practised for centuries within well-established (even if decentralised) normative consensus-based traditions, which isn’t the case in the UK. Of course, that isn’t to say that moonsighting can’t become a normative consensus-based process in the UK with an overall institutional or governance oversight, but the point is that it doesn’t today which is a challenge but also not a blank starting point.

- Muslims of the UK are not starting from a blank starting point. There are already various methods in play and many organisations and media outlets are involved that are independently doing their own things. Any new method needs to reconcile the conflicting nature of these methods across a diverse set of stakeholders. For example, both Wifaqul ‘Ulama and ICOPUK (Moonsighting.org.uk) have their own sighters across the UK (in addition to the New Crescent Society) who report sightings independently and receive faxes from the Morocco Awqaf Religious Ministry (which they publish instantaneously) to confirm positive and negative sightings. Some organisations like the infamously named Central Moon Sighting Committee of Great Britain and the Northern-based Jamiat Ulama-e-Britain simply follow Saudi hilal declarations. Then there is a multitude of satellite TV channels that relay news of Saudi hilal declarations, often by around mid-to-late afternoon. Many mosque-goers and committee members also have personal connections with those in Saudi Arabia who also relay information, which mosques independently or in association with their local mosque representation bodies take decisions locally. Then, there are others like Turkish-run mosques that simply follow whatever Turkey does, which is birth of the moon calculations which tends to be in line with Saudi hilal declarations (when based on the Umm al-Qura calendar). Given this, simply posing as a new organisation without reconciling in a syncretic manner will not help.

Why a narrowed definition of “local” is doomed to failure?

In my strategy paper in 2015, I looked at the idea of defining “local” to just the UK, but I found that it didn’t cut the mark of solving the problem in the UK. Here’s why:

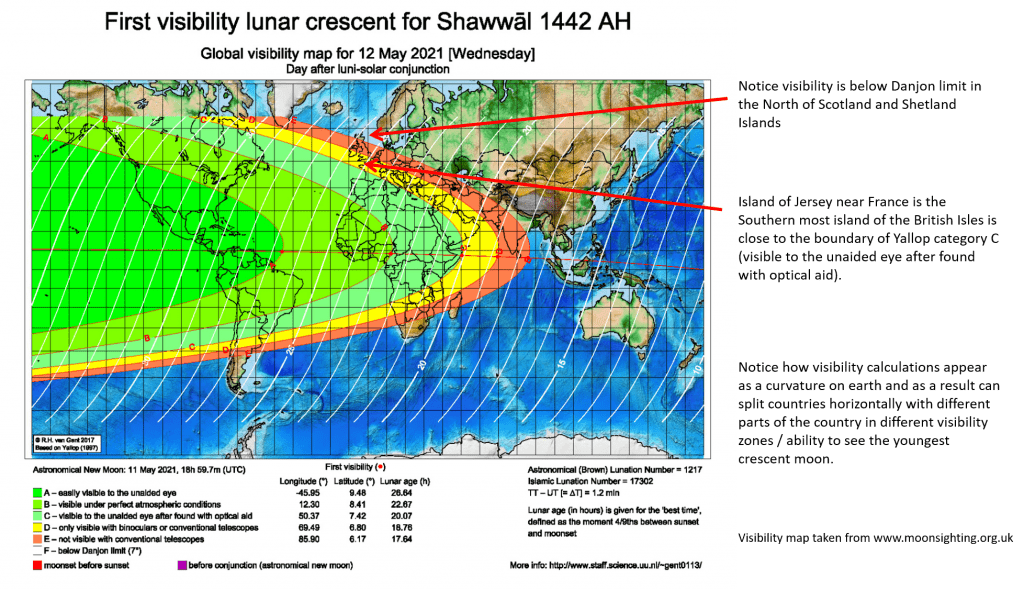

- Visibility sightings aren’t free of complications to do with what we mean by “local” and require judgements calls. The earth is spherical with a 5° title on its axis means that the area where the earliest time the crescent is visible is always a curvature that doesn’t necessarily align to nation-state boundaries – see example for Shawwal 1442 (2021). Meaning, it could be possible for the youngest crescent moon to be visible in some parts of the UK but not all (creating a horizontal divide). In such cases, what does it mean for those parts of the UK where it would have been deemed impossible to sight the crescent? If the answer is that they would take the outcome of positive sightings from another part of the UK where it was possible to sight the youngest crescent moon, then how is that any different in principle to what happens today with Morocco? Is nation-state the only difference here? What is the basis for negating science in this scenario? Moreover, isn’t it somewhat premature to claim the entire British Isles as a single sighting zone when there are no sighters in many places (like the Shetland Islands, North Wales, Guernsey, Scilly Isles, East Coast of England, many towns where Muslims live etc.) and certainly no where near compared to the well-established sighting zone of Morocco which has 14 zones and over 270 actual locations?

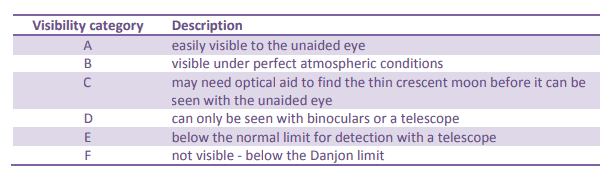

- Visibility calculations are themselves tricky. Visibility calculations have zones that are divided into categories or zones (see table below) based on the probability of sighting. One such example of this is the “Yallop criteria” devised by Dr Bernard Yallop and subsequently validated (and continues to be) using observation data. These zones can be tricky to interpret because there are different types of telescopes that can be used and at different altitudes. UK Muslims don’t use powerful telescopes in different sighting locations, and this can worsen their chance of seeing the youngest crescent moon.

- Designating the sighting zone area is complicated. As mentioned earlier, the designation of a sighting zone has always been subjective in Islamic history. There is nothing definitive (qat’i) that compels Muslims to absolutely follow a particularly narrowed viewpoint on “local” in the context of moonsighting, especially if it brings unnecessary burden and doesn’t take into account other more important contextual considerations (as happened in Eid al-Fitr 2021).

To demonstrate this subjectivity, let’s take the distance between London and the Shetland Islands which is about 800 miles in a northerly direction from London. But if we draw a circle with a radius of 800 miles from London, the region will cover Poznan, Poland, to the east and Barcelona, Spain, to the south. The question, then, is what makes it more justifiable for the small number of Muslims living in the Shetland Islands to follow sightings made in London versus someone in London following sightings in Southern France?

You could argue that Muslim countries use their geographic territory as the basis of the sighting zone which establishes the lawful precedent to replicate in the UK. However, as explained earlier there are some important differences that complicate comparison.

- The process capability for solely relying on UK sightings still isn’t quick enough and struggles to overcome expectation bias. I often get asked by mosque leaders in Luton to provide a synopsis of moonsighting prior to Ramadan and Eid. Speaking to them I get a sense that they’re wary of trusting people or organisations that they don’t have any personal contact with. Aside from a trust issue, the basic problem for mosque leaders in the spring and summer months is that news of the Saudi hilal declaration is always relayed by Muslim satellite TV channels broadcasting well ahead of sunset in the UK. This means that news from local moon sighters must always work against the expectation bias of people already presuming Ramadan or Eid. The resulting tumult and confusion (between individuals, mosques and from one town to the next) create its own momentum for quick decisions to be made.

- In the winter and autumn months, the UK’s cloudy conditions bring additional uncertainty in planning Ramadan and Eid. There have been plenty of months when visibility calculations deemed it possible to view the youngest crescent in the UK, but due to various reasons cloudy weather conditions, lack of moon-sighters, lack of powerful telescopes etc.) the crescent moon wasn’t sighted. It meant there were 30 days in the month, which, had it not been for cloudy conditions would have been 29 days aligning with those following Morocco or Saudi Arabia. Explaining this to mosque leaders or the average Muslim isn’t easy and brings chaotic weather-dependent uncertainties into planning.

- The average Muslim isn’t interested in the nuances of local and global sighting especially in the context of the UK’s Muslim communities organised along ethnonational lines. Often moonsighting organisations and enthusiasts get carried away with the importance that the average Muslim gives to the decision-making process or sighting the crescent moon. But the average Muslim has far more important matters and priorities to attend to. They simply want to know when Ramadan and Eid will start, and so long as they see close family and the mosque that they attend observe Ramadan and Eid together that is all that really matters. This is why British Bengali, -Arab, and -Somali communities across Britain, irrespective of internal or external theological differences, have always, and by enlarge, followed the simplicity of the Saudi hilal declaration, which has meant that they haven’t been divided on moonsighting, especially within the same town or city. Shared ancestral history and cultural factors drive uniformity. And for good reasons – people visit relatives at Eid who tend to be from the same ethnic background. Against this backdrop, any process that seeks to change this must be very simple and is able to get unanimous buy-in from Muslim communities across the UK.

- We are increasingly living in a more integrated and globalised world where information flows, ideas (on just about anything) and cultural exchanges criss-cross the boundaries of countries much more readily. News of global sightings tends to have its own inherent momentum partly because people want to feel connected with a global community of believers, and following Saudi Arabia is particularly useful because it is the land of the qibla and the Haramaym Sharifayn. Such inherent feeling of authority for local decision-making in the UK has yet to come about, as a result of poor religious literacy and weak religion-based intra-integration of ethnonational communities (despite the homogenising identity of the term “British Muslim”).

Only two things are clear from a Shari’ perspective. Firstly, that reports of hilal sightings are accurate (as reasonably as possible – this is subjective) and secondly that we achieve unity as Eid is a public event.

What should the New Crescent Society do to fix the problem?

I never thought I would have to write on this topic because, quite frankly, it is a minor issue that seems to take up too much time. But my disappointment at the New Crescent Society’s insistence on a narrowed definition of local and then going against a unified “one Eid” in the UK because it didn’t suit them was something that needed to be looked at.

I return once again to the humble idea of “practalism” at the heart of Islamic scholarship, which God teaches in the Qur’an and what the Prophet lived by. God doesn’t burden us beyond what is reasonable. The Prophet always looked for practical and unburdening solutions. Applied to this context, you could argue that for a small population of disparate Muslims from multiple ethnic backgrounds and priorities, evidently, it hasn’t been easy to cut through those differences to ensure alignment on moonsighting. To keep harmony, some Muslims, as a coping mechanism of sorts, against very visible divisions, have continued to maintain the validity of all opinions, encouraging a “do as your local mosque does” position. However, this passive position hasn’t improved the situation and merely kept Muslims pegged to the poor status quo. Yet, if we investigate Muslim history, where we find many differences on matters of religion, the division surrounding the start of Ramadan and Eid among resident neighbours is quite unheard of. It just doesn’t have a reasonable basis. And, in practical terms, too, there is still an unmet need to organise expediently for the purpose of planning in schools and workplaces.

The Shari’ah is solution-orientated and has many exceptions to general rules because circumstances necessitate local or dispensatory factors to be considered. With the spirit of this in mind, for moonsighting, three things should help.

- Moonsighting organisations should ensure they maximise the opportunity for achieving unified dates for Ramadan and Eid. To do this, they should align to a single two-step process for moonsighting.

- The first-step should be to look for the youngest crescent moon in the UK to confirm the hilal. Existing efforts should continue, improved, and expanded.

- The second-step should be to use reliable reports from abroad such as Morocco if it isn’t possible to sight the crescent in the UK.

- To help with the second step, moonsighting organisations should expand contractual relationships with groups and communities in easterly countries to import reliable (Shari’-based) news of hilal sightings, e.g. Southern France, Spain, North Africa etc. These relationships should be agreed-upon with all major moonsighting organisations in the UK, and must avoid what happened in one year where hilal sighting was unexpectedly imported from Uganda. If additional regions can’t be agreed upon, then Morocco should remain the only agreed-upon country. This way advocates of “local” sighting can maximise chance of unity across UK Muslims, whilst avoiding further splintering.

- Where it is clear that there will be a unanimous consensus on the day of Eid or start of Ramadan, moonsighting organisations should recognise that the Sunnah in that context is to join the unanimous consensus (jama’ah) and avoid causing confusion and doubt against the intent of the vast majority of Muslims.

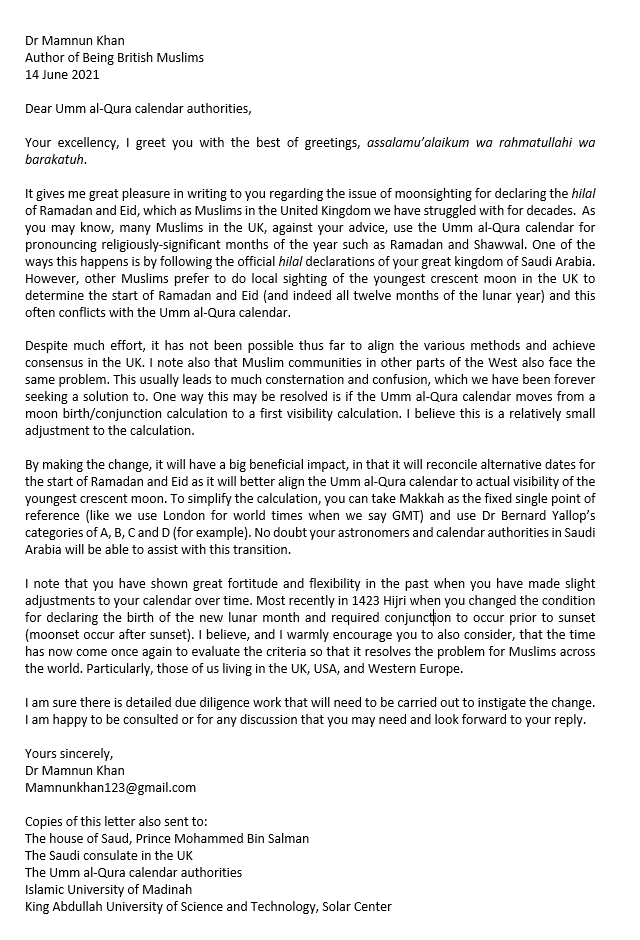

- Moonsighting organisations should lobby the Umm al-Qura calendar authorities to adjust their lunar calendar calculations from moon-birth to first visibility of crescent calculations. For simplicity, they can set the area as Makkah and include Yallop categories A, B, C, D. This will help reconcile differences between moon-birth and visibility sightings, improving the possibility for unified Ramadan and Eid in the UK and Muslims in Western countries (by the backdoor as it were).

On this point, I have written to the Umm al-Qura calendar authorities (see below) and await their response.

God knows best.

UPDATES:

- Since writing the blog, the ICOP UK member Qamar Uddin (http://www.moonsighting.org.uk) got in touch informing me that there are regular sighters in Jersey and other Channel Islands. In fact, there are now 130 different locations in the UK where regular moon sighting occurs. Qamar Uddin also mentioned that regional moon sighting (encompassing the UK, Western European countries and North Africa, or so) may well be the pragmatic acceptable middle ground in the long run. Of course that also deepnds on what happens with Saudi declarations.

- Rules such as: contractually-binding relationship; having a system of scientifically verifiable moonsighting setup; consistent process for 12 months of the year; integrity in the reporting process etc. For more details see Mufti Amjad Mohammad’s paper: The Islamic Calendar According to Muslims in the UK, Institute for the Revival of Traditional Islamic Sciences, 2015, http://www.irtis.org.uk.

One Response

Isn’t it just better to be united? If Saudi say the moon has been sighted, then surely a few hours later when it’s our sunset, the moon will also be there? If they are wrong, surely it’s not a sin on us who are trying to keep the unity of the Muslim Ummah. Didn’t our Prophet (saw) forbid fasting on Eid? So on both Eids, if the people of the land are celebrating should not the others put their differences behind and celebrate together? Now we can watch the hajj live, the day of Arafat can be seen, yet some in UK still choose to do it a day later? Where is the reasoning? What about the Hadith about remaining united?